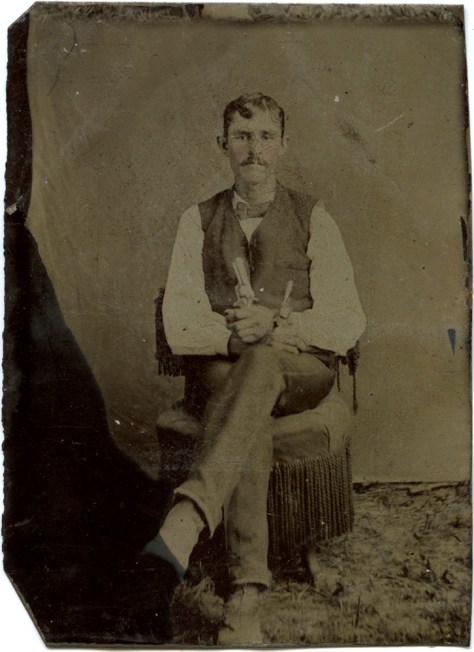

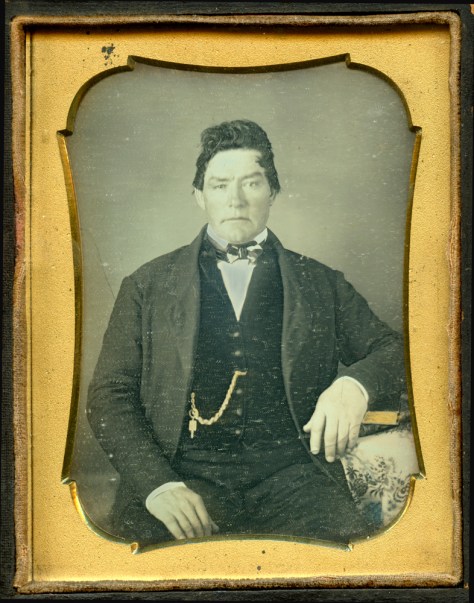

Here are three of my latest collecting acquisitions. First, the daguerreotype. A very nice quarter-plate dag, extremely well exposed, and very subtly hand-tinted and gilded. If you look carefully you can see the hands are flesh-toned, and the face has a hint of it as well. The gentleman’s watch fob and the edges of the book pages are gilded. Both of these touches would have been “up-sells” at the time of the commissioning of the image. I haven’t popped this one out of its case yet because the glass is resting directly on the mat, and not bound by a brass frame as part of a package, and the glass is in so tight that I’d be afraid of cracking it or tearing the velvet surround trying to get it out. The scan does not do it justice, as the scanner’s lens can’t quite focus on the image plane.

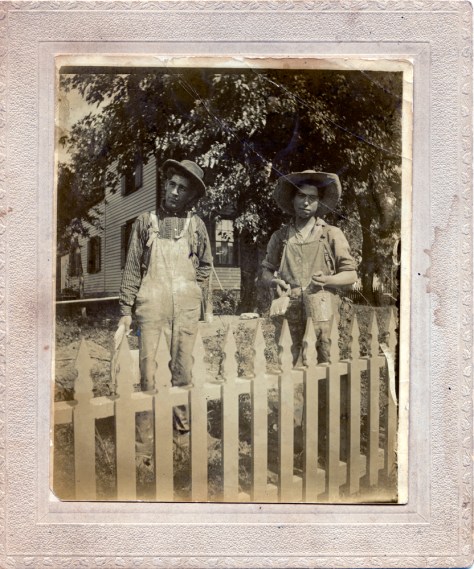

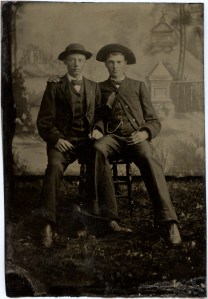

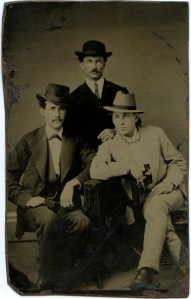

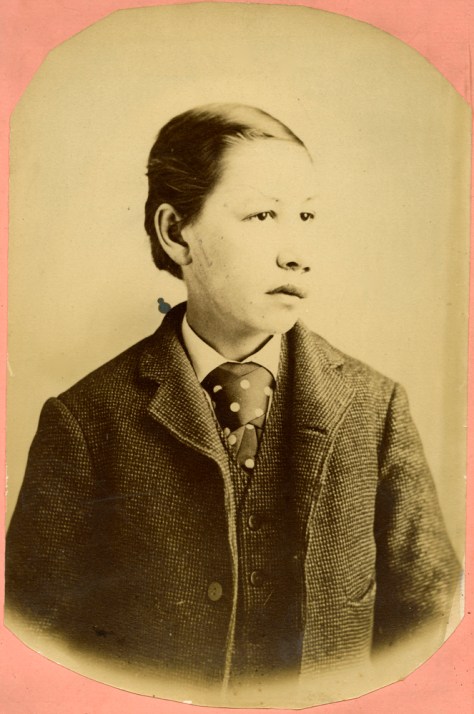

Next up are a pair of rather fun images. They’re totally anonymous, both from a photographer’s and a subject’s point of view. The why of collecting them is rather simple – they’re interesting. And they were bargains. Bought off Ebay, they sold at the right (wrong from the sellers’ perspective) time of day and attracted no other bids, so I got them for a penny apiece. You don’t have to spend a lot of money to start collecting, and these are proof. The thing that grabbed my attention about both of these initially were the auction titles- “African-American/Native American man” and “Two Men doing a Tom Sawyer”. I’m deleting the seemingly obligatory “rare” from the titles because EVERYTHING on Ebay is “rare”, and if it doesn’t look like a dog chewed on it, it’s also “minty”. Minty describes a flavor or odor, not a condition. These are both obviously not “minty”, but that’s ok – what counts is the image itself. While a pristine image is a beautiful thing to find, I also enjoy finding photos that look like they’ve had a life, and were not just bought and stuck in an album on a hidden shelf.

On the “African-American/Native American man” photo, it is an albumen print, and there are some obvious mis-handling marks from the time of printing (see the silver splotch over his shoulder). I will grant the “rare” on this one as images like this are while perhaps not truly “rare” they are uncommon. I’m actually on the fence about who and what this young man might be. The straight hair suggests Native American, but some of the facial features like the nose and cheekbones could be African or even Asian features, and certainly very likely to be mixed race of some sort. Guessing from the attire (and PLEASE correct me if I’m wrong) this was taken in the 1890s.

The last image has no other way to describe it but “FUN”. Two men white-washing a fence, posing with their paint cans and brushes. A real slice of Americana, I love the sense of humor about it as well as the pop-culture reference before there was such a concept as a pop-culture reference. I’m sure Tom Sawyer would have had a good laugh at this if he were real, to see it. It even looks like the depictions of Aunt Polly’s house from movies. This is on silver gelatin “gaslamp” paper, and mounted on embossed card stock. I’ve tweaked the scan a bit to improve the picture quality overall, so don’t entirely trust the color balance.