Being a photographer who teaches, I have a lot of friends who are themselves photographers. It gives me lots of opportunities to photograph them, often with their cameras. It can get rather meta-referential, but that’s part of the fun.

This is Mari Calai, one of the members of the Handmade Photography Group at Glen Echo Photoworks. She’s also the current Artist-In-Residence at Photoworks.

Colin Gore waiting around for one of the other photographers in the Handmade group to do his portrait in Wet Plate Collodion. The group did an outing in February to the National Gallery of Art and then brunch afterwards.

Paige Billin-Frye, another group member and fellow instructor – she does amazing hand-colored and toned cyanotype work. It was interesting to see how many of the group members were using small (meaning medium format film or smaller) cameras on that outing. I was the only one shooting 6×7 (my new-to-me Pentax 67) – everyone else was shooting 6×6 square (mostly Rolleiflexes) or 35mm/full frame digital, except Mac who was shooting 5×7 wet plate.

Speaking of, there Mac is in action, shooting his portrait of Mari.

The man, the myth, the legend, not buried under a barkcloth. It was February, it was 45 degrees farenheit, and he was wearing sandals without socks.

Chris Gumm, who coincidentally practices gum bichromate printing, posing with his Rolleiflex.

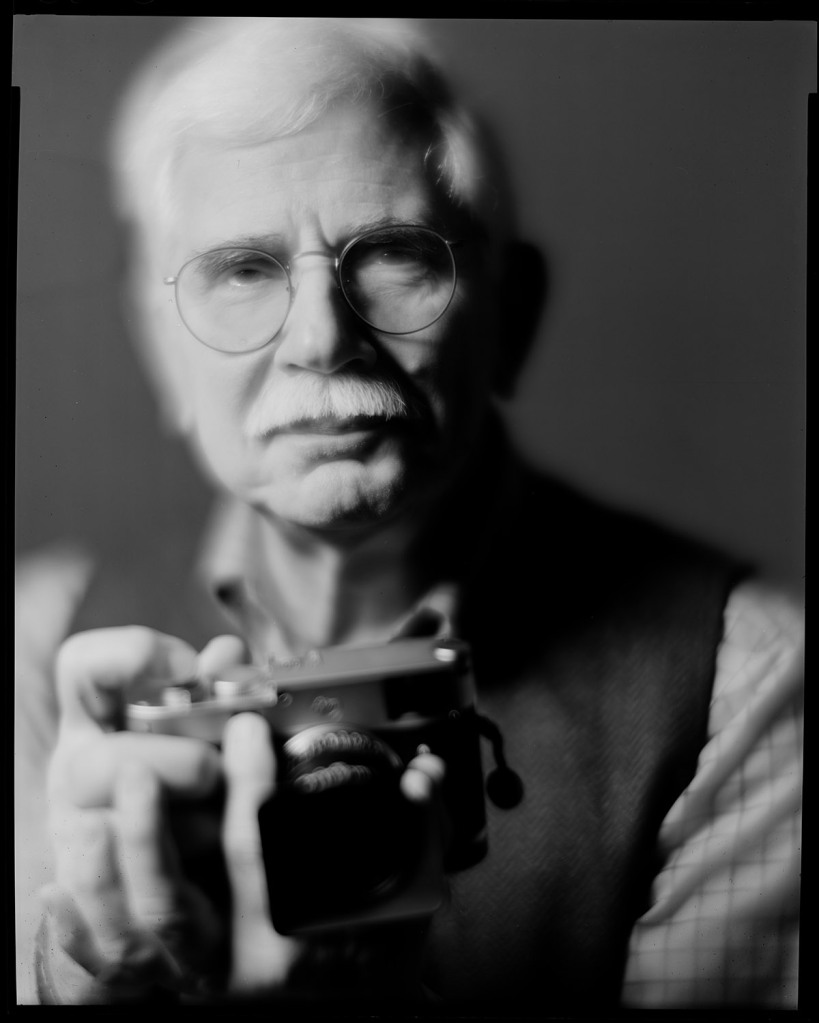

Switching gears somewhat, Steve Greenberg is another one of the Photoworks people, but not part of the Handmade group. This was from a commissioned portrait sitting we did, this time with my 8×10 Century Master studio portrait camera and the Kodak 405mm Portrait lens.

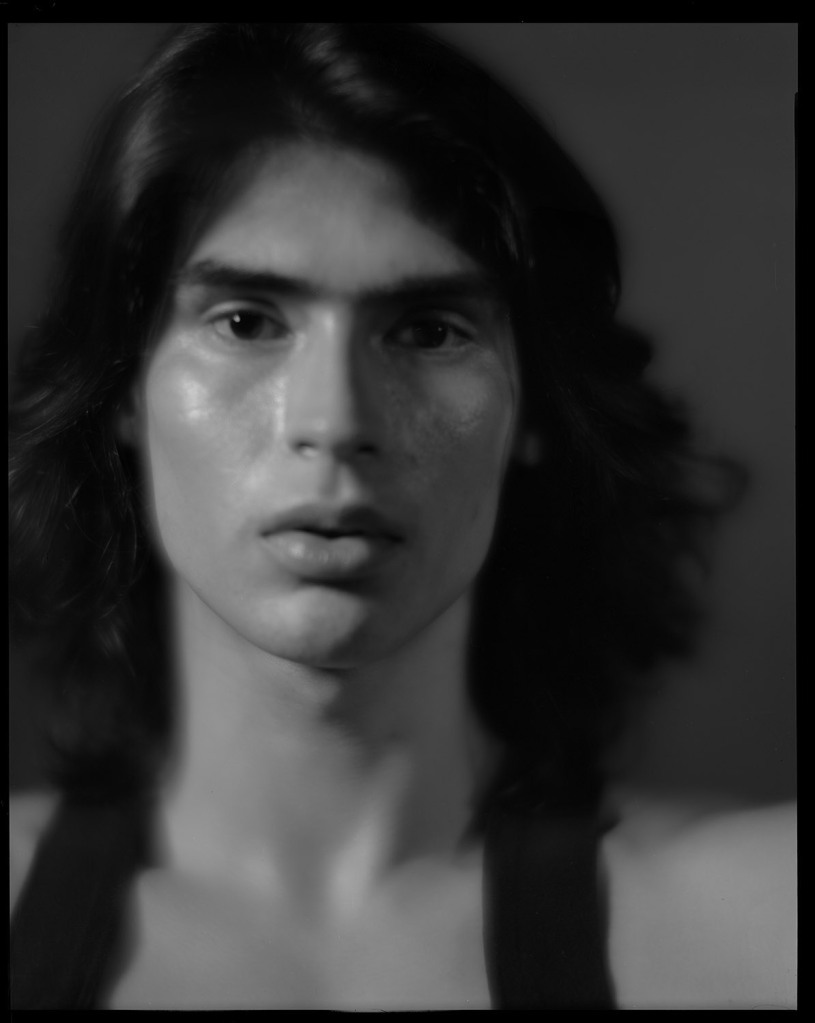

A different take on Steve, with a different camera and lens – still a soft focus portrait lens, but this time the Pentax 67 120mm soft focus portrait lens. It’s a lens that surprised me – I picked it up because I liked the soft focus effect I was getting on the Kodak Portrait and with some of the smaller soft-focus lenses I have (the Hermagis Eidoscope, a Seneca Whole Plate aka Wollensak Vesta, and my Cooke Series II, which isn’t technically a soft focus lens but has really creamy out-of-focus rendering especially wide open). I wanted to see how good it would be for this effect on a small format. It’s going to stay in my arsenal of lenses, and actually stay in my camera bag unless I KNOW I won’t need it for a particular trip. It requires careful use to get the best out of it – you control the soft focus through the use of the aperture, where wide open is the fuzziest/glowiest, and once you get below f/8, it’s mostly tack sharp. Best used in the studio, where you can control the amount of light you feed it, especially with how relatively fast modern films are.

One parting shot, very meta-referential, as it’s a photographer in a photo studio, showing the fact that it’s a photo studio.