Otherwise known as: Scott was a very bad boy 🙂

I went to the DC Antique Photo Show today. The show took up three meeting rooms at the Holiday Inn Rosslyn. Two smaller rooms were devoted to postcard collectors, and the much larger main room was strictly photographic images. I toured the entire show, but got a bit lost in the detail with the postcard dealers – there’s just way too much material to look through! My intent was to try and hunt down a couple stereoviews for my set of Lehigh Valley Railroad stereoviews, but that thought quickly went out the window when it could have taken the entire day to just sift through the stereoviews of just two or three vendors.

I did find something pretty cute and nifty though – a woman there, the mother of one of the Civil War image vendors, was making and selling (very cheaply) little fabric pouches for storing cased images. I bought four to cover my thermoplastic cased daguerreotypes. The pouches are made of color-fast fabric (it feels like a good-quality felt). The 1/6 plate size are $1.50 each – if you’re interested, let me know and I can send you the lady’s email. I won’t post it here, out of respect for her, so she doesn’t get bombarded by spammers.

In the main room is where I got in trouble. It started with a book – “Shooting Soldiers” by Dr. Stanley Burns. The book is about the history of medical photography during the Civil War. Dr. Burns is a SERIOUS collector of antique images, and has amassed an astounding collection of Civil War period medical images, among other topics. The images in the book are from his collection. He himself was there at the show, and autographed the book for me.

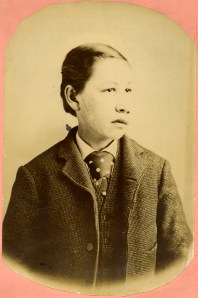

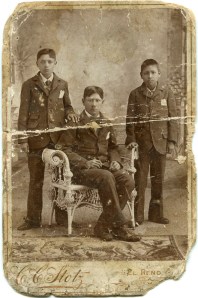

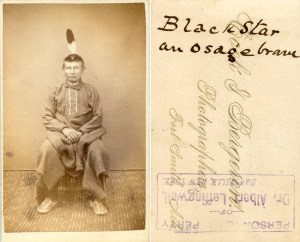

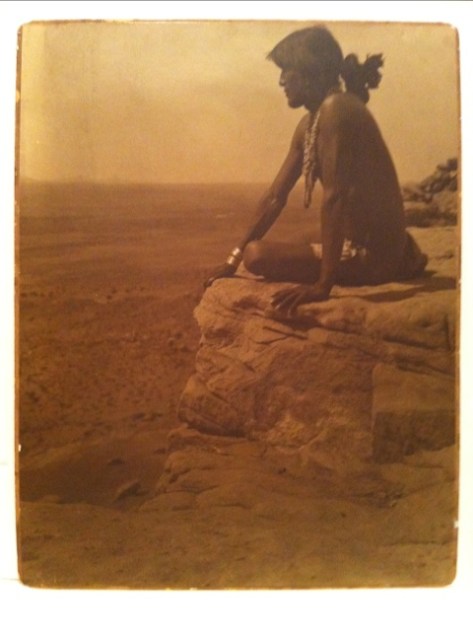

Across the way there was a booth selling native american images, and CDVs. Would that my budget could have stretched this much, but alas, the Alexander Gardner CDV of Vice President (and later President) Andrew Johnson was not to leave the show in my hands. I did acquire a nice period CDV of two musicians, one seated, the other standing, holding his violin.

The vendor indicated that the duo was famous in their day. When I asked who they were, he didn’t know either, but acted as if I should somehow know myself! Sorry, but I haven’t kept up on mid-19th century performers. Have you? If someone out there in collector-land does recognize them and can pass it on, it would be much appreciated!

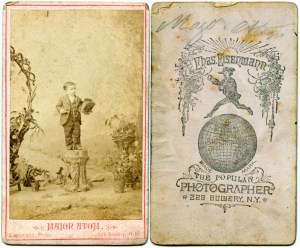

At another booth I found a neat addition to my circus freaks collection – another midget, Major Atom! And it gave me yet another address for one of my New York studios to put on my map – Chas. Eisenmann, “The Popular Photographer”. I love the advertising slogans these photographers came up with – it’s a little window on the Victorian era mindset.

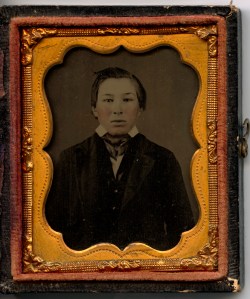

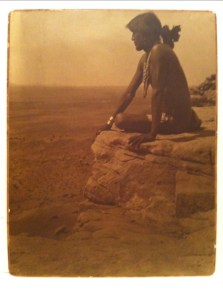

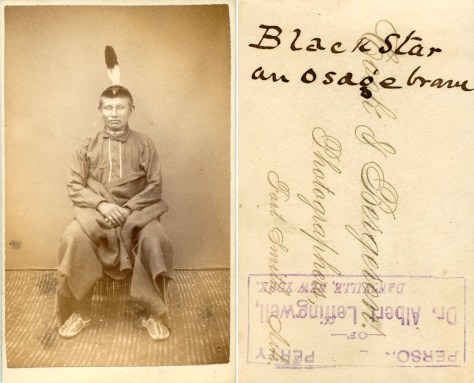

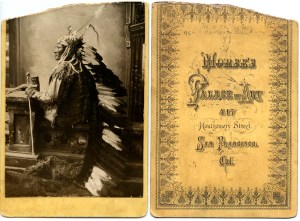

I found a famous Native American cabinet card – “Rain-in-the-face”, taken at Morse’s Palace of Fine Art in San Francisco. Rain-in-the-face was a cohort of Sitting Bull, a war chief of the Hunkpapa Sioux. He was one of the warriors responsible for Custer’s defeat. It’s a beautiful image, and although the card is damaged, the damage doesn’t significantly detract from the quality of the portrait.

Well, if I got me an Indian, I had to get me a Cowboy! This one is looking just a little bit gay.

I have no idea if in fact he was gay, but by 21st century sensibilities, he’s a little too well put together, he’s gripping his pistol in an oh-so-suggestive manner, and those chaps!

I must put in a plug for someone at the show – he was not only a vendor of antique images, he’s also a modern-day Daguerreotypist himself. Casey Waters does modern daguerreotypes using mercury development, which by itself is cool because it’s the REAL way to make a daguerreotype. But even cooler, among other things, he’s done night-time daguerreotypes – I pity his car’s battery because I can’t imagine how long the headlights had to be on in order to record the image on the plate.

To check out his work, you can visit Casey Waters Daguerreotypes (the night-time daguerreotypes are nine rows down from the top of the page, on the left and center columns).

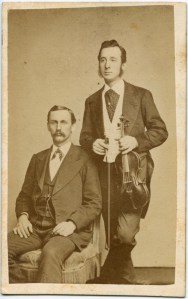

Last but not least, there was a Tom Bianchi print I picked up. There is a little damage to the print (which I touched up in the scan), which is why I was able to get it so cheap. It’s also marked as 4/5 Artists Proofs. Which means that Tom Bianchi gave it away to someone, it wasn’t sold commercially. The damage is minor, and easily repairable, so I may actually try to retouch it myself.