A reblog of the article in full from the Ohio State Historical Society on Tintypes.

Category Archives: Collecting

A little corrective history

Someone who shall remain unidentified was selling a tintype on eBay. I won’t describe the image in detail, except to say that the subject matter was of sailors. There was a unique identifying feature in the photo that had the potential to point either to World War I or the Civil War. In doing a tiny tiny bit of basic (wikipedia) searching, the more logical conclusion is WW I. The seller had it labeled as a civil war image. I emailed him and pointed out the reasons why the image was WW I. His response back was “I know of no WW I era tintypes as the process was obsolete by the 20th century”. The tintype was around as a souvenir photo at carnivals and fairs into the 1930s. I have some tintypes in my collection that show people with cars. I know I shouldn’t pick fights with people on stuff like this- I don’t care about what it sells for and I don’t want to disrupt this guy’s business, but inaccuracy with something like this rankles me, moreso when it’s caused by unwillingness to do basic research, and even moreso when it’s done out of greed. A WW I tintype of sailors is probably worth $20-50. A Civil War tintype of sailors, tack at least another zero on those numbers, and depending on condition and quality, possibly two more zeros.

Here’s a good simple reference on the history of the tintype, if anyone is interested:

Quarter plate Daguerreotype, Lady with Glasses

The newest addition to the collection. She arrived today in USPS. I love the simple gesture of pointing to the glasses, as if to indicate a prized possession.

The scan again does not do justice – it picks up and magnifies every little dust fleck. I’m not going to bother cleaning the dust off because this one still has the complete intact original paper seals on the packet. This one is circa 1840-45, closer to ’45 than ’40 based on the style of the mat. The truly early images had very simple mats with just the top corners rounded, or an elongated octagon for the opening, and usually with either a smooth but matt finish or a pebble-grain texture to the mat.

Book Review – Preserving Your Family Photographs by Maureen A. Taylor

In an effort to better understand how to care for the variety of images I’ve been collecting, I found a volume on Amazon entitled “Preserving your Family Photographs” by Maureen A. Taylor. Billed as “the nation’s foremost historical photo detective” (Wall Street Journal), I had high expectations for the volume. A historical photo detective she may be, but able to ferret out a good publisher and editor she is not. There is too much repetition of certain points (don’t attempt conservation/restoration work yourself, hire a professional conservator), not enough detail on certain others, and very poor copy editing – frequent typographical errors and larger mistakes like doubling the contents of a table. All of these should have been remedied by an attentive copy editor and/or layout production team. Other mistakes are things like when referencing a vendor for a product (protective storage boxes for cased images), in the text of the volume, she refers readers to the Appendix. In the appendix, a list of archival product vendors are listed, without reference to which products are being offered at each vendor, requiring readers to browse the website of every vendor to find sources. Another mistake is in listing vendors without vetting them – Light Impressions being a prime example. A formerly reliable vendor of outstanding products, for several years now they have become increasingly unreliable, with business practices of a dubious ethical and legal nature (charging customers in full for orders even when products are on back-order, not notifying customers of back-order status, and not refunding money for back-ordered products until the products are in stock). While I understand that there is a definite cost to including color photo illustrations in a printed book, if you are attempting to describe the kinds of deterioration various types of photographs undergo, it is far more helpful to show full-color illustrations of these changes, because the intended audience for this book is not a curator or serious collector, but instead a John or Jane Q. Public who has found a trove of family photos and wants to organize and protect them.

Another bone to pick I have is with discussions of “scrapbooking”. I know that this can be done in a more archival way, especially now that people are more conscious of archival preservation issues and that products that ARE archival are available. To me, “scrapbooking” still brings to mind construction-paper cut-outs, paste glue, pinking shears, black photo corners and silver glitter pens. As someone interested in photographs as complete objects, that’s fingernails on a chalkboard. The idea of trimming a photograph to fit in an unused corner of the page is antithetical – especially if the trimming may remove some meaningful detail or an inscription on the back that could help identify dates, locations or identities. I’ve seen too many of those old black paper albums from the 1910s to 1950s where things were glued in and the writing on the back was completely obliterated by the black paper permanently adhered to the back of the photo.

Thinking of black paper albums, one interesting fact mentioned in the book is that unless the album is in such poor condition overall that it is putting the photos in jeopardy of being bent, torn or otherwise damaged, you are just as well off leaving them in the black paper album so that you do not lose the context of any labels written in the album and of the surrounding images that might help identify the subjects. This is the first time I’ve seen it stated as such, and while from an historian’s perspective, that makes a lot of sense, at the same time, I’d like to see an independent confirmation of this statement that the black paper pages are sufficiently stable as to not do long-term harm to photos stored thereon.

I’m probably not the target audience for this book, as pretty much everything she said was non-revelatory to me. If you are an average Joe looking to preserve and protect family photos, then once you get past the production values issues with the book, there is a lot you can learn without feeling like you’re taking a college-level materials science or chemistry course. For someone with more experience as a collector and/or photographer and is familiar with archival preservation materials and techniques, this book is too basic.

A Visit to the DC Antique Photo Show

Otherwise known as: Scott was a very bad boy 🙂

I went to the DC Antique Photo Show today. The show took up three meeting rooms at the Holiday Inn Rosslyn. Two smaller rooms were devoted to postcard collectors, and the much larger main room was strictly photographic images. I toured the entire show, but got a bit lost in the detail with the postcard dealers – there’s just way too much material to look through! My intent was to try and hunt down a couple stereoviews for my set of Lehigh Valley Railroad stereoviews, but that thought quickly went out the window when it could have taken the entire day to just sift through the stereoviews of just two or three vendors.

I did find something pretty cute and nifty though – a woman there, the mother of one of the Civil War image vendors, was making and selling (very cheaply) little fabric pouches for storing cased images. I bought four to cover my thermoplastic cased daguerreotypes. The pouches are made of color-fast fabric (it feels like a good-quality felt). The 1/6 plate size are $1.50 each – if you’re interested, let me know and I can send you the lady’s email. I won’t post it here, out of respect for her, so she doesn’t get bombarded by spammers.

In the main room is where I got in trouble. It started with a book – “Shooting Soldiers” by Dr. Stanley Burns. The book is about the history of medical photography during the Civil War. Dr. Burns is a SERIOUS collector of antique images, and has amassed an astounding collection of Civil War period medical images, among other topics. The images in the book are from his collection. He himself was there at the show, and autographed the book for me.

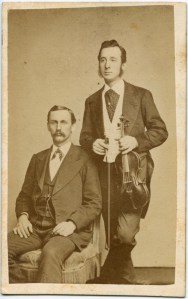

Across the way there was a booth selling native american images, and CDVs. Would that my budget could have stretched this much, but alas, the Alexander Gardner CDV of Vice President (and later President) Andrew Johnson was not to leave the show in my hands. I did acquire a nice period CDV of two musicians, one seated, the other standing, holding his violin.

The vendor indicated that the duo was famous in their day. When I asked who they were, he didn’t know either, but acted as if I should somehow know myself! Sorry, but I haven’t kept up on mid-19th century performers. Have you? If someone out there in collector-land does recognize them and can pass it on, it would be much appreciated!

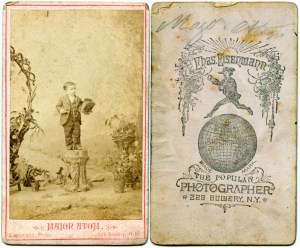

At another booth I found a neat addition to my circus freaks collection – another midget, Major Atom! And it gave me yet another address for one of my New York studios to put on my map – Chas. Eisenmann, “The Popular Photographer”. I love the advertising slogans these photographers came up with – it’s a little window on the Victorian era mindset.

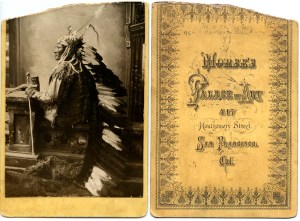

I found a famous Native American cabinet card – “Rain-in-the-face”, taken at Morse’s Palace of Fine Art in San Francisco. Rain-in-the-face was a cohort of Sitting Bull, a war chief of the Hunkpapa Sioux. He was one of the warriors responsible for Custer’s defeat. It’s a beautiful image, and although the card is damaged, the damage doesn’t significantly detract from the quality of the portrait.

Well, if I got me an Indian, I had to get me a Cowboy! This one is looking just a little bit gay.

I have no idea if in fact he was gay, but by 21st century sensibilities, he’s a little too well put together, he’s gripping his pistol in an oh-so-suggestive manner, and those chaps!

I must put in a plug for someone at the show – he was not only a vendor of antique images, he’s also a modern-day Daguerreotypist himself. Casey Waters does modern daguerreotypes using mercury development, which by itself is cool because it’s the REAL way to make a daguerreotype. But even cooler, among other things, he’s done night-time daguerreotypes – I pity his car’s battery because I can’t imagine how long the headlights had to be on in order to record the image on the plate.

To check out his work, you can visit Casey Waters Daguerreotypes (the night-time daguerreotypes are nine rows down from the top of the page, on the left and center columns).

Last but not least, there was a Tom Bianchi print I picked up. There is a little damage to the print (which I touched up in the scan), which is why I was able to get it so cheap. It’s also marked as 4/5 Artists Proofs. Which means that Tom Bianchi gave it away to someone, it wasn’t sold commercially. The damage is minor, and easily repairable, so I may actually try to retouch it myself.

The New Dags, and the original Tintype that started it all…

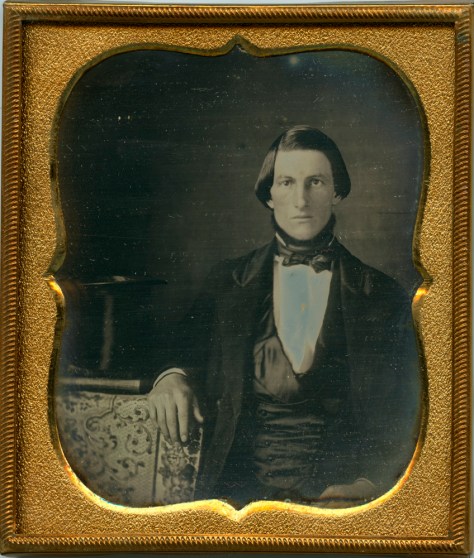

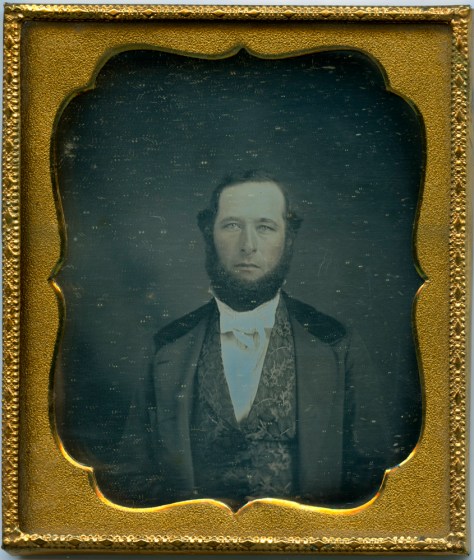

Here are the three new daguerreotypes that arrived yesterday. The scans do not do them justice, as they pick up every fleck of dust and scratch and magnify them, plus the images themselves are slightly soft due to being just out of the scanner’s focusing range. They’re all 1/6 plate daguerreotypes in full leather cases. Mrs. A.A. Hill and the gentleman with the top hat have had their seals replaced and glass and mats cleaned recently. The anonymous gentleman in the fancy vest still has his original seals on the packet. Given that the cases of the two gentlemen’s photos are almost identical (same style of mat and packet frame, same style of case lining – plain red silk), the odds are in favor of them both having been made within a year or two of each other – the gent in the fancy vest would have been photographed sometime between 1847 and 1851.

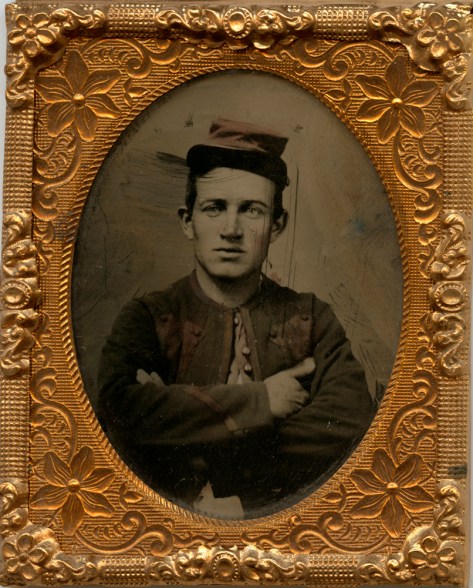

And last but certainly not least, is the photo that started it all. This was the first image I ever “collected” – it was an inheritance from my grandmother. Alas she did not get to tell me what if anything she knew about him, as it came to me shortly before she passed away. Thanks to a friend who is a serious civil war buff and re-enactor, I have been able to put some information together about who he might be. The soldier was a member of the 76th Pennsylvania Zouaves, who trained and fought in Moroccan-style uniforms adopted from French Zouave units. Zouaves (pronounced zoo-ahh-vah), patterned after the French Zouaves, were elite units especially popular in the Union Army. They were known for their precision on the drill field and for their colorful uniforms consisting of gaiters, baggy pants, short red jackets with trim, and turbans or fezzes.* Given the area of Pennsylvania in which my family lived, he was probably a member of Company B, D or E of the 76th Pennsylvania. The 76th Pennsylvania was involved in a number of major conflicts during the Civil War, including the assault on Fort Wagner (made famous in the movie Glory where the 54th Massachussetts (the first authorized all African-American unit) won their honor in the assault on the ramparts), Drewry’s Bluff, Cold Harbor, the siege of Petersburg, the battle of Fair Oaks, and the surrender of Johnston’s army. As typical, they lost more men to disease than to combat – 161 killed vs 192 laid low by disease. The officers fared better- 9 killed vs. 2 lost to illness. I don’t know for certain, but I believe my ancestor was one of the survivors.

According to my friend, this image was made in late 1861 or early 1862, as the uniform changed over the course of the war to more closely resemble the standard Union blue uniforms. Also, in this picture he looks to be in the peak of health. Most veterans by late in the war were looking rather thin, and on the Confederate side, downright malnourished.

The photo is a 1/9th plate tintype in a half-case – the case is designed to look like a miniature book, but now the front cover has gone AWOL.

If anyone can help identify him more specifically, your assistance would be GREATLY appreciated. The last name would most likely be Berger (or a spelling variation on the same) or Riley. Davies is also possible, but less likely as I think the Davies branch didn’t immigrate to the US until the 1870s, but that could be wrong.

It COULD be George W. Reilly of Company E, but according to the records I found, he entered service in 1865, as a substitute for someone else who was drafted, so the early uniform date would not make sense.

It could also be James D. Davis or George Davis, who were Corporals in Company C, but the spelling of the name is wrong for the time period.

Another possibility is James P. Davis of Company K. Again, the spelling is wrong, but the location is a fit – Company K was organized in Schuykill County, which is where the Davies branch of the family lived. Two other Davises, Robert and Isaac, are listed as privates in Company K, but both were killed in action. So I’m a bit confused as to who he might have been. He’s got some kind of rank insignia on his sleeve, but it is only one stripe, and Union corporals had two stripes. In the modern Marine Corps, lance corporals get a single stripe, but this is not a Marine uniform. So herein lies a giant mystery.

Collection summary

I received three more daguerreotypes in the mail yesterday, and that inspired me to do a mini inventory of the daguerreotype and other cased images collection. Don’t take my collection as being statistically accurate as to the population of cased images out there, but the general trend is I think illustrative of the market in general.

1/9th Plate

- One milk glass ambrotype in oval velvet pushbutton case

- Two ambrotypes in gutta percha/thermoplastic cases

- One daguerreotype in leather case

- Two tintypes in half leather cases

1/6th Plate

- Three daguerreotypes in half leather cases

- Four daguerreotypes in gutta percha/thermoplastic cases

- Twelve daguerreotypes in leather cases

- Two ambrotypes in leather cases

- One ambrotype in leather case

- One ambrotype in gutta percha/thermoplastic frame

- One ambrotype in brass mat, missing frame or case (most likely frame)

- Four tintypes in leather cases

1/4 plate

- One daguerreotype, missing case

- One daguerreotype, in half leather case

- Three daguerreotypes in leather cases

- One ambrotype, in half leather case

1/2 plate

- Two ambrotypes in leather cases

So, forty-two cased images altogether, with twenty-eight being 1/6th plate. Seventeen ambrotypes/tintypes, twenty-five daguerreotypes. Thirty-four in some form of leather case, seven in gutta percha/thermoplastic. I’m making a distinction between a half leather case and a whole leather case only from a collectors perspective – the half-cases are images whose cover was separated from the image at some point in time and not retained. Daguerreotypes are over-represented in the collection because that’s what I’ve made an effort to collect. There are probably more cased tins/ambros out there than daguerreotypes. 1/6th plate dominates, because that was the most common size produced. 1/9th plate is probably less uncommon than my collecting habit would indicate, again because of personal taste. The 1/4 plate and larger, though, are far less common. Prices have ranged from as little as free (one is an inherited piece) to $300 (which believe it or not was not one of the half plate images). Most have been in the $30-$150 range. Most images are by undocumented photographers of anonymous subjects, but perhaps four have the sitter identified, and I have one by Plumbe, two by Brady (although one of the Bradys may not be, as the case halves are different), one by Judson of Newark, NJ, one by Clark of New Brunswick, NJ, one by Kimball of New York, NY. One is from Argentina, the rest are American. One is allegedly Ulysses S. Grant’s niece. One is definitively dated 1849. Several others are probably older, including the Brady and Plumbe daguerreotypes, but most are from the 1850s.

On another date, at a different time, I’ll inventory the CDV/uncased image collection, which is much larger and more diverse.

Anonymous Daguerreotype

Just another random daguerreotype. I was drawn to the image by the hand-coloring which is subtle, unlike some I’ve seen where it can get over-the-top, and the flaw in the hand-coloring – notice that her face was nicely tinted, but they forgot to do her hands!

I’m no fashion expert, so I can’t give you more precise information about dating the image based on the wardrobe of the girl, but from the style of the dag itself, you can tell this one is from the 1850s – the mat itself is ornate and highly tooled, and the packet is wrapped in a gilt brass frame. Early daguerreotypes (1839-mid 1840s) have very simple geometric mats, often with a pebble texture. As the 1840s turned into the 1850s you get the thermoplastic cases and the more stylized mats, and ending with the ornate mats and packet frames. Tooled leather cases continue side-by-side with the thermoplastic cases through the Daguerrian era and on into the end of the cased tintype era, so using the case itself to date the image is not sufficient. If I can find my reference book that has a timeline of the evolution of photographic presentation styles, I’ll amend this to clarify when thermoplastic cases came into being and when they died out, but that could be a while – my library is a bit higglety-pigglety right now as I’ve run out of shelf space (2000+ volumes will do that to you).

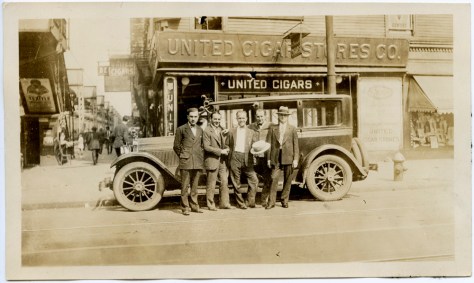

Fun with old cars

Yet another topic to collect – old car photos. I’ve had an obsession with cars since I was a kid – my dad had a 1955 Ford Thunderbird that he restored, and that sparked the passion. In high school, I drove a 1962 Nash Metropolitan until my parents decided it was unsafe and made me get a used Honda instead. Which turned out to be far more unsafe than the Met, because it was capable of going fast :). For your appreciation, here’s a 1920s Packard, and a 1911 Cadillac.

The Packard photo is clearly a snapshot, having been made with a smaller camera and printed by machine on thin gaslamp or other silver gelatin paper. The Cadillac photo is more of a formal portrait, contact printed and mounted on heavy card stock, taken with an 8×10 view camera. The owner would have been extremely proud of his car to have taken that photo, as the level of effort and expense to do it were considerable. And in November of 1911, he would have been justifiably proud of that car – Cadillacs have always been expensive luxury cars, but in 1911, a car like that would have been a truly rare thing and extremely expensive. By the early 20s when the Packard photo was taken (the car looks like it is somewhere in the neighborhood of 1923-25), not only was photography more accessible to a mass market, so were cars – even Packards were more commonplace, and they were direct competitors to Cadillac, if not considered superior. Packard was one of the three “P’s” of the great automobile manufacturers of the 1910s and 1920s – Packard, Peerless and Pierce Arrow. By the 1930s, Peerless was gone, and Pierce Arrow was on the ropes, to vanish as a manufacturer by the onset of WW II (although their 12-cylinder engine continued on in production in one form or another into the 1980s as the power plant for fire trucks).

More updates to the Victorian Photographers maps

I’ve added four more studios to the New York and three to the Philadelphia Victorian photography studios maps.

New York:

- William J. Tait, corner Greenwich & Cortlandt streets

- John C. Helme – Daguerreotype studio, 111 Bowery

- Abraham Bogardus – Daguerreotype studio (early), Greenwich & Barclay

- Mathew Brady – Daguerreotype studio (early), 205-207 Broadway

Philadelphia:

- D.C.Collins & Co. City Daguerreotype Establishment, 100 Chestnut Street

- Reimer, 612 N. 2nd Street

- Van Loan & Ennis – Daguerreotype studio, 118 Chestnut Street

Just a little more fun with the photographers maps compilation.

Here’s a quick link to the maps in case:

Some more food for thought – I think I’ve mentioned this before, about the migration over time of certain studios, moving uptown in New York as their client base moved further uptown – to better illustrate this, I’ve pulled the studio addresses for three of the most prominent portrait studios of the day, and listed them in chronological order as best possible:

Mathew Brady:

- 205-207 Broadway

- 359 Broadway

- 635 Broadway

- 785 Broadway

Gurney & Sons

- 349 Broadway

- 707 Broadway

- 5th Avenue & E. 16th Street

Abraham Bogardus

- Greenwich & Barclay Streets

- 363 Broadway

- 872 Broadway

Also notice how close they all were to each other. While I don’t have dates per-se for each of the addresses, notice that at one point, all three were in the same block of Broadway (the 300 block), and again later, all three were in a two block span of Broadway, further uptown (700-800 block). Even early on, they were clustered close to each other in Lower Manhattan – 643 Bleecker is not far from Greenwich & Barclay, and another photographer, William J. Tait, was just a block or two away at Greenwich & Cortlandt streets.