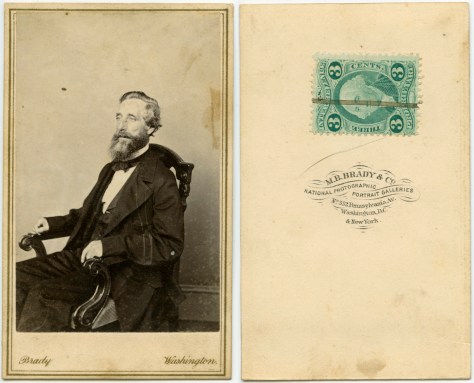

Here’s another Brady CDV from the Washington DC studio. Anonymous subject.

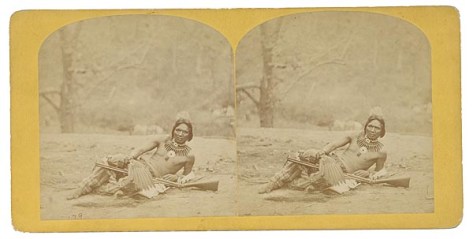

Here’s a vintage stereoview of Chief Standing Buffalo (although he’s not standing in this image) from 1871. This is a perfect example of what I was just discussing in the comments on the last post – this is a copy stereoview of an original. You can tell this is a copy by the overall lack of sharpness and contrast, and by the fact that the card is completely unlabeled as to subject or photographer. An original card from the original photographer would fetch something 6-10 times what I paid for this one.

Here is a scan from a 2008 auction catalog of the original stereoview, by Hamilton & Hoyt. Notice the difference in quality.

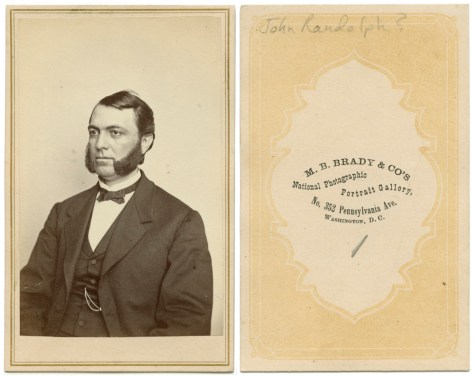

Two more CDVs – a Brady from the DC studio, and judging by the backmark style, a later (post Civil War) image. The sitter is reputed to be named John Randolph, one of the FitzRandolphs of Philadelphia (or could it be the FitzRandolphs who gave the original land grant to found Princeton University?). Evidence is unclear, but the picture is very.

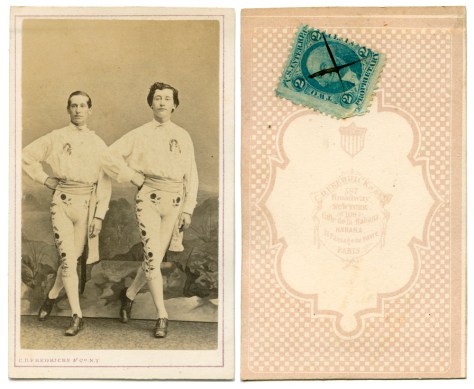

The second CD is from the Fredericks studio, of New York, Havana and Paris. As the subject is toreadors, I’m guessing this was taken at either the Paris or Havana studios. Bullfighting has never had any serious following in the United States, so toreadors would be unlikely to come to New York on a performing tour of the US. I thought I had another Fredericks CDV somewhere in my collection, but I’ll be damned if I can find it – I may have just recorded the address on my New York studio map during a scan of studio backmarks on eBay.

This is another image that could have been marketed as “gay interest”, thankfully it wasn’t. Despite their costumes and matching fey poses, there’s nothing about them that shouts (or whispers) 19th century code for gay. Pure 21st century wishful thinking.

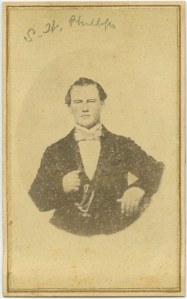

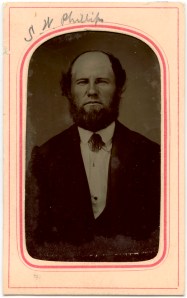

Here’s a fun little trio of cartes-de-visite, showing the same sitter what looks to be covering a span of 20 or more years. In the first one, Mr. S.W. Phillips of Baltimore appears youthful. In the second one, the card-mounted tintype, a bit older, sporting a rather tall top hat. And in the third photo, a definitely older Mr. Phillips has lost not only his hat but his hair.

|

|

|

I had to fight to keep all three together – the image with the top hat was of much interest to other buyers. I was willing to go a little over what I’d wanted to spend to keep the set, as I thought it would be a real shame for the other two to get separated where they’d linger in someone’s $5 box, unloved, unwanted and without context. As an erstwhile photo historian, all too often these kinds of things get lost because someone removes the context for the sake of the value of a single item.

On a separate note, almost totally unrelated to the rest of this post, sometimes I wish I had enough info to start a Baltimore photo map like my New York, DC and Philadelphia maps. I’m certain that there were many photographers there in the 19th century, as Baltimore was a much more important city at that time and a major hub of commerce and industry. Perhaps this can be a start – the Edkins Gallery at 103 Baltimore Street. If anyone out there in blog-land has studio addresses for Baltimore Victorian photo parlors, I’d love to have them so I can start the map!

Another genre of tintypes to collect is the “trickster”. These could be anything from examples like these where the photographer switched heads on bodies in the shot (don’t ask me how, my guess is it involved re-photographing a dissected original) or people dressed in drag, to modern-day ones like someone wearing victorian period costumes but sporting a digital watch or an iPod.

Little loose tintypes like these (approximately 2×3 inches each) are generally a very affordable entree into collecting. These are both probably from the 1890s/early 1900s.

Here are two tintypes that would probably get listed on eBay as “gay interest”. The one appears to me to be pretty obviously a father and son posing in formal wear. The other is much more ambiguous – is it a trio of gay couples? Just six friends stopping by the tintype parlor on a lark? One of the men in the front row appears to be clenching a cigar in his fingers, and two of the men in the front row seem to have some kind of numbers chalked on the soles of their shoes (who knows what it is, if anything). Also very odd is the staging- the men in front look like they’re sitting on the floor, but the men behind them appear to be standing upright, not sitting or kneeling. Are the two men in the front row (left and center) brothers? Inquiring minds want to know!

Last but not least, aren’t you glad swimwear has evolved since the 1880s? How’d you like to go for a dip in the ocean and have to wear that stuff? It’s bad enough when your swim trunks dry out and get salty – imagine that feeling all over! And how long would it take for what looks like wool to dry after a thorough immersion in salt water? You’d be as likely to catch pneumonia from the swimsuit!

Edit > Ok – this is an update of this post – the earlier one was only the last 30 days statistic. This is all-time hits. Quite a few more total visitors and quite a few more countries. </Edit

I had a friend of mine who works for the UN, stationed in the Sudan visit my blog today, so I thought I’d go take a look at the site stats and see where my visitors are coming from. Some of the numbers are not surprising at all, and others are quite surprising.

Countries I expected volume from are pretty obvious, but Saudi? Iraq? Nigeria? Trinidad? Wow! And that I had more visits from Sudan than from New Zealand? (Well, I know why I had more visits from Sudan, but still…) Now if I could only get a fraction of these folks to COMMENT! 😀

| Country | Views |

|---|---|

| 485 | |

| 74 | |

| 44 | |

| 35 | |

| 24 | |

| 21 | |

| 17 | |

| 17 | |

| 16 | |

| 16 | |

| 13 | |

| 12 | |

| 11 | |

| 8 | |

| 7 | |

| 7 | |

| 6 | |

| 6 | |

| 5 | |

| 5 | |

| 4 | |

| 3 | |

| 3 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 |

A reblog of the article in full from the Ohio State Historical Society on Tintypes.

Someone who shall remain unidentified was selling a tintype on eBay. I won’t describe the image in detail, except to say that the subject matter was of sailors. There was a unique identifying feature in the photo that had the potential to point either to World War I or the Civil War. In doing a tiny tiny bit of basic (wikipedia) searching, the more logical conclusion is WW I. The seller had it labeled as a civil war image. I emailed him and pointed out the reasons why the image was WW I. His response back was “I know of no WW I era tintypes as the process was obsolete by the 20th century”. The tintype was around as a souvenir photo at carnivals and fairs into the 1930s. I have some tintypes in my collection that show people with cars. I know I shouldn’t pick fights with people on stuff like this- I don’t care about what it sells for and I don’t want to disrupt this guy’s business, but inaccuracy with something like this rankles me, moreso when it’s caused by unwillingness to do basic research, and even moreso when it’s done out of greed. A WW I tintype of sailors is probably worth $20-50. A Civil War tintype of sailors, tack at least another zero on those numbers, and depending on condition and quality, possibly two more zeros.

Here’s a good simple reference on the history of the tintype, if anyone is interested:

The newest addition to the collection. She arrived today in USPS. I love the simple gesture of pointing to the glasses, as if to indicate a prized possession.

The scan again does not do justice – it picks up and magnifies every little dust fleck. I’m not going to bother cleaning the dust off because this one still has the complete intact original paper seals on the packet. This one is circa 1840-45, closer to ’45 than ’40 based on the style of the mat. The truly early images had very simple mats with just the top corners rounded, or an elongated octagon for the opening, and usually with either a smooth but matt finish or a pebble-grain texture to the mat.

In an effort to better understand how to care for the variety of images I’ve been collecting, I found a volume on Amazon entitled “Preserving your Family Photographs” by Maureen A. Taylor. Billed as “the nation’s foremost historical photo detective” (Wall Street Journal), I had high expectations for the volume. A historical photo detective she may be, but able to ferret out a good publisher and editor she is not. There is too much repetition of certain points (don’t attempt conservation/restoration work yourself, hire a professional conservator), not enough detail on certain others, and very poor copy editing – frequent typographical errors and larger mistakes like doubling the contents of a table. All of these should have been remedied by an attentive copy editor and/or layout production team. Other mistakes are things like when referencing a vendor for a product (protective storage boxes for cased images), in the text of the volume, she refers readers to the Appendix. In the appendix, a list of archival product vendors are listed, without reference to which products are being offered at each vendor, requiring readers to browse the website of every vendor to find sources. Another mistake is in listing vendors without vetting them – Light Impressions being a prime example. A formerly reliable vendor of outstanding products, for several years now they have become increasingly unreliable, with business practices of a dubious ethical and legal nature (charging customers in full for orders even when products are on back-order, not notifying customers of back-order status, and not refunding money for back-ordered products until the products are in stock). While I understand that there is a definite cost to including color photo illustrations in a printed book, if you are attempting to describe the kinds of deterioration various types of photographs undergo, it is far more helpful to show full-color illustrations of these changes, because the intended audience for this book is not a curator or serious collector, but instead a John or Jane Q. Public who has found a trove of family photos and wants to organize and protect them.

Another bone to pick I have is with discussions of “scrapbooking”. I know that this can be done in a more archival way, especially now that people are more conscious of archival preservation issues and that products that ARE archival are available. To me, “scrapbooking” still brings to mind construction-paper cut-outs, paste glue, pinking shears, black photo corners and silver glitter pens. As someone interested in photographs as complete objects, that’s fingernails on a chalkboard. The idea of trimming a photograph to fit in an unused corner of the page is antithetical – especially if the trimming may remove some meaningful detail or an inscription on the back that could help identify dates, locations or identities. I’ve seen too many of those old black paper albums from the 1910s to 1950s where things were glued in and the writing on the back was completely obliterated by the black paper permanently adhered to the back of the photo.

Thinking of black paper albums, one interesting fact mentioned in the book is that unless the album is in such poor condition overall that it is putting the photos in jeopardy of being bent, torn or otherwise damaged, you are just as well off leaving them in the black paper album so that you do not lose the context of any labels written in the album and of the surrounding images that might help identify the subjects. This is the first time I’ve seen it stated as such, and while from an historian’s perspective, that makes a lot of sense, at the same time, I’d like to see an independent confirmation of this statement that the black paper pages are sufficiently stable as to not do long-term harm to photos stored thereon.

I’m probably not the target audience for this book, as pretty much everything she said was non-revelatory to me. If you are an average Joe looking to preserve and protect family photos, then once you get past the production values issues with the book, there is a lot you can learn without feeling like you’re taking a college-level materials science or chemistry course. For someone with more experience as a collector and/or photographer and is familiar with archival preservation materials and techniques, this book is too basic.