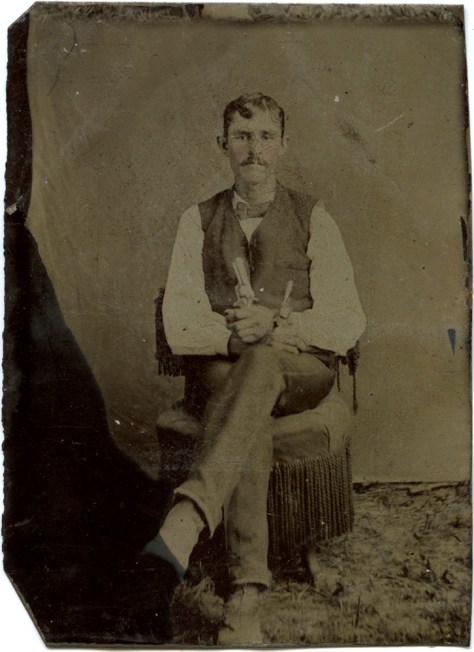

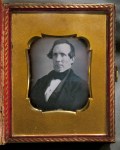

On November 23, 2011, David Prifti, a brilliant wet-plate photographer living, working and teaching in the Boston area, passed away after an extended battle with cancer. I am deeply saddened that such a bright light and creative force for positivity has gone out. I knew his work from APUG, Large Format Info, and the Collodion Forum, but never had the chance to meet him in person. I have seen his plates live though, hanging on gallery walls, and no web reproduction can do them justice. You can see his work online at the three previously mentioned websites (all linked from here). His work was part of the Masterplaters show that just closed November 22 at the Community College of Baltimore County Catonsville campus. Plans are in the works to bring the exhibit to the Washington DC area in the not-too-distant future – keep an eye on this blog for future information. There will be a memorial service on November 30th 4pm at the First Parish Unitarian Church in Concord, MA.

Upate 11/29/2011: Here is a link to a short writeup on the Huffington Post about David:

David Prifti, 1961-2011

There will be a scholarship fund established and named after him at the school where he taught. Information on donations is available in the linked article above.