Serendipity plays a major role in my life. A couple weeks ago I took a mental health day mid-week and decided to visit some of our local history. My original intent was to take a short road trip to see some historic houses in northern Virginia, but they (the Woodlawn Plantation and the Pope-Leighy House) were still closed for the season. Instead, I thought I’d take a quick drive down Indian Head Highway into southern Maryland and visit Fort Washington, created to defend the capital city from river attack in the early days of the Republic. The current structures date from the years after the War of 1812 to the first decade of the 20th century. The main fort was designed by Pierre L’Enfant, the man who laid out the design for the streets of Washington DC.

On the drive down Indian Head Highway, after only a mile or so I saw a sign saying “Fort Foote Park”. I decided I’d detour and check it out. I really didn’t know much of anything about Fort Foote other than I presumed it was part of the Civil War-era defenses of Washington DC. My presumption about it was correct, but there’s a lot more to it than you might expect given that description. Most of the 68 defensive forts that ringed DC are now little more than some mounded dirt with a plaque commemorating what they were. They’re overgrown with trees and grass and cross-cut with walking trails, city streets, and even housing developments. Fort Stevens, the location where the only sitting United States President ever came under enemy fire, today is barely a half a square block, hidden behind a post-war church, 20th century homes and shops, and hemmed in by city streets.

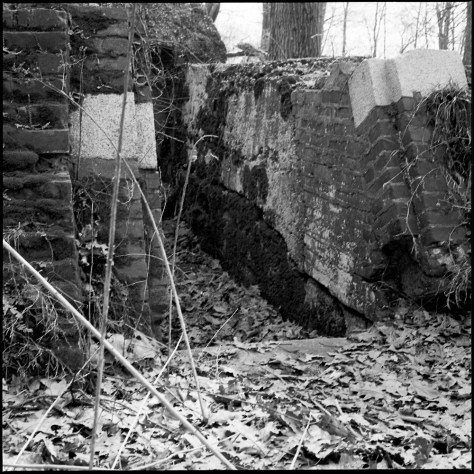

Fort Foote has been spared much of that indignity. Fort Foote (named after a Union admiral who was killed in action in 1863 assaulting Confederate strongholds on the Mississippi river) too is overgrown with forest, but the earthworks remain very much in their original configuration. It owes its survival in part due to the location on a 100 foot tall bluff facing the Potomac river, too awkward a site for proper development. Two of the mighty 15 inch Columbiads (also known as Rodman guns for the man who designed them) remain in situ, and the ammunition vault’s crumbling ruins (also known as a “bombproof”) can be seen and scampered over by enterprising and nimble youth.

The Rodman gun was a major innovation in cannon technology. Due to a radical change in forging technique, they could be made much stronger and safer to be fired repeatedly without risk of the powder charge exploding the gun itself. The design was so successful that eventually the United States had nearly 450 of them providing coastal defense. The 15 inch Columbiad version could fire a 200 pound projectile some 5000 yards and penetrate ten-inch steel armor at that range. The guns at Fort Foote were never fired in anger. The smaller 12 inch and 8 inch cannons that topped the earthworks were removed by the end of the 19th century when the fort was decommissioned. Today, only a handful of the 15 inch Rodman guns remain in existence, the majority having been melted down or in some cases entombed in concrete to add support to the improved fortifications they once defended.

The notches on the back of the Rodman gun, along with the large, relatively flat “knob”, are signatures of the design, and indicative of some of the innovations. By making the “knob” large and flat, it made it much easier to hoist the cannon for moving it and loading and aiming – a common problem with smaller guns that had a much more traditional knob on the rear was that the weight of the gun, when hoisted in the air, would stress the join between the barrel and the knob and it would break, sending the extremely heavy barrel crashing to the ground, crushing anyone below, ruining the gun, and possibly discharging the shot if it were loaded.

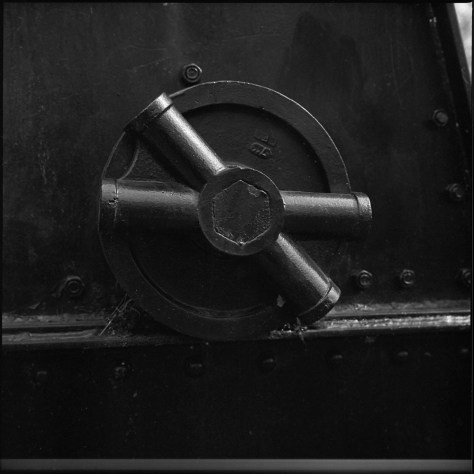

The Rodman cannons were mounted on platforms that would enable them to be withdrawn below the earthworks to be loaded, and then raised when ready to aim and fire, reducing the exposure of the gunnery teams to enemy small arms fire. This wheel with its tubes to take wooden levers would have been used to raise and lower the gun on the pop-up mount.