Everyone-

Everyone-

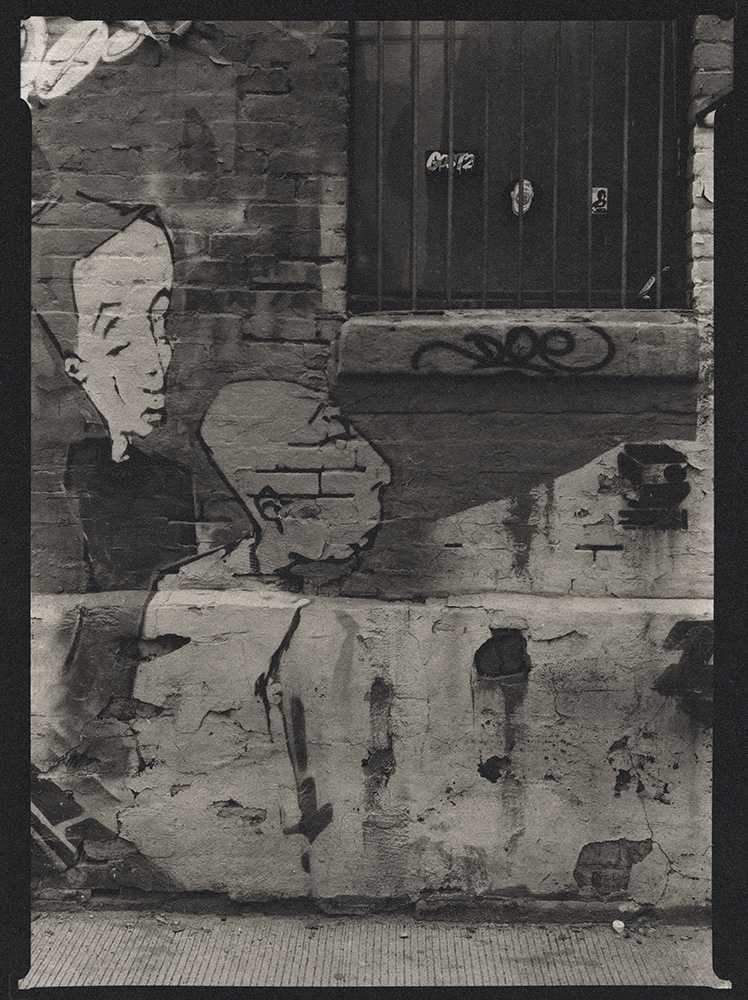

In my latest iteration of my Intro to Platinum/Palladium printing class, I dug up some old negatives I had made, since my student this time was sufficiently skilled with wet darkroom processes and not interested in getting into shooting large format (in my standard group class, we take my Canham 5×7 out around Glen Echo and make a dozen or so negatives for students to work from). This was a print from that session.

It’s a memorial to the transitions on U Street. This is graffiti art that has since been obliterated by gentrification and re-development – the alley where this was has been re-graffiti’d, but with “sanctioned” artwork a bit more sanitized and easier to interpret.

This print is a 5×7 palladium print. The usual chocolate-brown color is missing because I gave this emulsion mix a shot of NA2 contrast agent to give it a bit more snap. The NA2 contains platinum, which is what cools off the image and makes it more neutral. If you’d like to learn how to print this way, contact me through the blog and we can schedule a class, either one-on-one or I can fit you in to an upcoming class at Glen Echo Photoworks.

I have some very exciting news to announce – my upcoming Introduction to Platinum/Palladium Printing class is now sponsored by Hahnemuhle, makers of fine art printing papers since 1584. They recently introduced a new paper specially formulated for alternative process printing, specifically platinum/palladium, and are graciously supplying the class with a very generous stock of paper for the students to use. I hope this will be the beginning of a long and fruitful partnership.

Could you tell me your name?

Hendrik Faure

Where are you from?

Germany

How did you get into photography as an art medium (as opposed to casual or professional use)?

I do not remember for sure, I have a darkroom since 1966 and soon was interested in fine art printing, made solarisations and lith-printing. Later I hand-coloured my still life photographs.

Which alternative processes do you practice?

copperplate photogravure following method of Talbot/Klic.

What attracted you to alternative processes in general?

Interest in photohistory and in aesthetic well composed pictures.

What drew you to the specific media you practice?

Pictorialistic photogravures in literature and museums.

How does the choice of media influence your choice of subject matter (or vice versa)?

The medium fits the message.

In today’s mobile, electronic world of instant communication and virtual sharing of images, how important is it to you to create hand-made images?

Important enough to spend three days work per print edition

Is your choice to practice alternative, hand-made photography a reaction to, a complement to, or not influenced by the world of digital media?

When I began photography, there was no digital. Later I had my first computer. It was a Tandy TRS 80 model 3 and already had a mouse. She crawled through the floppy drive slot and tragically died within. I suppose, then the mouse did not like computers. I made some stills with dead mice. This was the strongest influence of digital media to my work.

Do you incorporate digital media into your alternative process work?

Photogravures need an inter-positiv, which I make chemical-based on document-film or digital on pictorio ohp. Digital so-called full frame cameras give freehand a quality like 24x36mm film cameras on tripod, but tend to have no soul.

I use digital capture sometimes if film is not possible. In the scrap project I captured pictures as well electrical as film-based (middle-format to 8x10inch).

If so, how do you incorporate it? Is it limited to mechanical reproduction technique, or does it inform/shape/influence the content of your work?

I use digital media for inferior photowork and seldom for multimedia projects.

What role do you see for hand-made/alternative process work in the art world of today? Where do you see yourself in that world?

This may be decided some 50 years later

If you’ve never curated a group show before, especially one with international reach, it’s hard to imagine the level of effort that goes into putting on an art exhibit. You have to put out the call for entries, manage the publicity to make sure you get enough work submitted to fill the walls even after reviewing and editing, and then handle the acceptance emails and collect the accepted work.

Oh, and be prepared for things not working out as planned. I feel extremely lucky we had only two hiccups with submitted work. One was minor – one piece of work came off its mounting in transit. With a quick email to the artist, I got his permission to open the frame and re-mount the work properly so it would present well on the wall. In the process, I also replaced the source of the problem (gummy adhesive squares that were NOT archival) with water-activated linen tape loops using acid-free wheat paste for adhesive. No artist’s work is going to be damaged by me on my watch!

The second hiccup was totally beyond anyone’s control, which is what made it so maddening. Yugo Ito’s photograph coming from Japan was shipped in plenty of time to arrive at the gallery. However, it got stuck in customs in New York for almost two weeks. There was nothing to be done but to wait, as customs is a black hole into which things enter and exit at their own pace and there is no transparency or communications possible beyond checking the tracking number on the USPS website. Creativity saved the day, though – since the actual work was not in the gallery for the opening, I took the JPEG of the work from the submission and printed it, mounting it to the wall with a sheet of glass and some L-pins. It would be represented in spirit even if not in actuality.

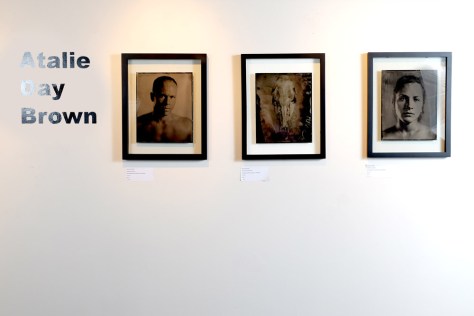

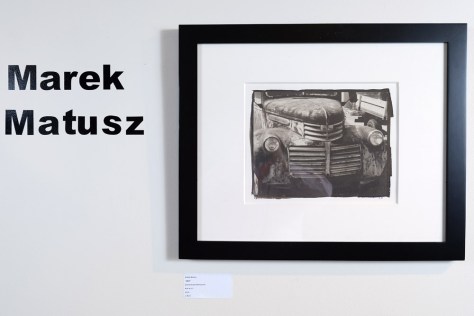

Once all the work has arrived, you have to plan how you’re going to hang it. You can look at JPEGs all you want, and generally gauge which artist’s works should hang next to which other artist, but the actual sequencing and spacing can’t really be figured out until you have the actual framed work in hand at the gallery. Next it’s measure, measure, measure, and then plan, and re-measure, before driving the first nail into the wall. Having gallery interns to help with the hanging makes life so much easier (Shout-out to my interns! Thank you!!).

Now the work is all hung, you can relax, right? NO. Then it’s plan the reception, send out the invites, send out the press releases, buy too much cheese and crackers at Costco, and then throw a party. There’s the curator’s remarks to prepare, and handouts about the work to write. Oh, and blogging about it all the while!

At some point during the show, ideally right after you’ve hung the work but before the public comes in to see it, you document the exhibit. Below are a few excerpts from the show as hung. One of the great challenges of curating a show is that once you have it up on the wall, what might look good in the space presents a wicked challenge to document. Trying to photograph pieces in corners where you can’t get a light on them from the other side means that you’ll either have dramatic falloff in the scene from one side to the other, or you’ll have a hideous reflection of your umbrella or other diffuser in the picture glass. I opted for a bit of falloff rather than reflections where possible because the falloff can be compensated for to a degree in Photoshop – a big blinding white reflection of an umbrella cannot.

You’re not done until the show is over, the work taken down, and the artists have picked up their work or you’ve shipped it off to hither and yon. Then you get to relax for a day or two, and if you’re a busy curator, it’s back to the process all over again!

Could you tell me your name?

Marek Matusz

Where are you from?

Residing and working in Houston, TX

How did you get into photography as an art medium (as opposed to casual or professional use)?

That went hand-in -in hand with the discovery of alternate processes

Which alternative processes do you practice?

Just about anything: platinum/palladium, silver/iron processes, chrysotype (gold), gum bichromate

What attracted you to alternative processes in general?

I was attracted to the chemistry at first and then the aspect of creating one of a kind hand made images

What drew you to the specific media you practice?

Platinum and palladium prints were are of the technically most accomplished and able to produce most delicate highlights and deep shadows. Seeing great examples of early XX century work in museums and galleries made mu pursue the process . I have started over 25 years ago and the information back then was scant and confusing

How does the choice of media influence your choice of subject matter (or vice versa)?

When taking and composing a picture I try to visualize which alternative process would fit, whether I wand process edges showing, etc.

In today’s mobile, electronic world of instant communication and virtual sharing of images, how important is it to you to create hand-made images?

Two aspects are important. Education of consumer in the existence and quality of hand made images and history of photography through a practice of XIX century processes. The second is keeping and enlarging patron/collector market. Real collector wants something to be touched and held in hand, not a shared digital image.

Is your choice to practice alternative, hand-made photography a reaction to, a complement to, or not influenced by the world of digital media?

It would be totally silly to ignore the digital world. It exists regardless of our feelings about it (good, bad??). SO with that respect it is just a complement. But it is also a strong protests against huge color enhanced digital prints that have invaded galleries.

Do you incorporate digital media into your alternative process work?

Yes, I use the technology as a toll. Some of my captures are digital, most of my negatives are created with digital processes. I am also not against digital alterations of the photograph in the process of creating a picture

What role do you see for hand-made/alternative process work in the art world of today? Where do you see yourself in that world?

I see myself as a part of alternative photography movement. A small (by digital standards) but growing group of practitioners and educators that shares information, practices and the word of photography at its roots

What is your name, and where are you from?

Bruce Schultz from Lafayette, Louisiana.

How did you get into photography as an art medium (as opposed to casual or professional use)?

I’ve always taken photographs for myself as an artistic expression, since the early 1970s.

I make images with wet-plate collodion to make tintypes on metal, or ambrotypes on glass, or glass negatives to make paper prints in the form of salt prints and albumen prints. I have one salt print and three albumen prints in this show, all from glass negatives.

What drew you to the specific media you practice?

I grew bored with making black and white images with film, printed onto factory-coated silver gelatin paper, something I had done for almost 40 years. As digital photography had emerged as the dominant means of making pictures, I regressed and sought out the basics of photography as it was first practiced. So I took a workshop in Missouri with wet plate photographer Bob Szabo in 2007.

Since then, I no longer shoot film. I make tintypes at civil war reenactments, and also photograph a wide range of subject matter from still lifes, landscapes and nudes. I’ve made images for movies (“Beautiful Creatures” and a remake of “The Magnificent Seven.”) And TV shows including “American Horror Story” and “Into the Badlands,” in addition to several CD covers.

How does the choice of media influence your choice of subject matter (or vice versa)?

Since my chosen process requires exposures of several seconds to minutes, action can’t be photographed but even that can be overcome if one is willing to invest in a high-powered, eyebrow singeing flash equipment. I will occasionally pay homage to 19th century images.

In today’s mobile, electronic world of instant communication and virtual sharing of images, how important is it to you to create hand-made images?

I’m not opposed to digital photography, and I use it in my career as a communications specialist, but digital imagery is too realistic, too perfect for my purposes. With wet-plate collodion, serendipitous flaws are inherent in the process. Fingerprints, smudges on the edges, specks of dust, bubbles, scratches, are inevitable and they make it obvious that this is a one-of-a-kind handmade image never to be repeated.

Is your choice to practice alternative, hand-made photography a reaction to, a complement to, or not influenced by the world of digital media?

I don’t really think about the digital realm, what I’ve done digitally or anyone else has done with a digital camera. I do often marvel that in the time span that I make one image with the wet-plate process, someone could shoot hundreds of pictures. Because of the labor and time involved to set up the chemicals and equipment, making an image with the wet-plate process is a deliberative effort. One has to make sure that what has caught their eye is truly worth the effort and time to make just one picture.

And I have to admit that I get some kind of rush from knowing that I’m making photographs the same way that the early photographers did, experiencing the same frustrations when things go wrong, and the same tingle of excitement when everything comes together. Using the same formulae and materials but with the benefit of modern technology like air conditioning in a darkroom and electric lights.

Do you incorporate digital media into your alternative process work?

I have made digital prints from my wet plate images, but they do not equal a print from a wet-plate negative and I no longer do that because the quality is inadequate.

If so, how do you incorporate it? Is it limited to mechanical reproduction technique, or does it inform/shape/influence the content of your work?

I want to learn to make digital negatives from tintypes to make albumen and salt prints. I am even willing to attempt using digital capture to generate a digital negative and from that, make albumen and salt prints, especially for images that I make while traveling abroad since flying on airplanes can’t be done with flammable chemicals and hundreds of pounds of equipment.

What role do you see for hand-made/alternative process work in the art world of today?

Sales of vintage photography have increased with higher and higher prices as buyers recognize the significance of photographs that have survived for more than a century..

Alternative process work has emerged as a significant movement as the art audience recognizes the effort and dedication required to generate these images. And shows like this one illustrate that more people are creating bodies of work based on handmade imagery.

That’s not to say that serious artistic expressions can’t be the product of digital capture, but so many images are being created digitally that we are being overwhelmed with snapshots fired in scattergun fashion. I’ve read that more photographs have been taken in the past 2 years than in the first 150 years of photography. I’m not sure how that figure was derived, but it is mind-boggling. But most of those images will never move beyond a phone or computer screen, and it’s expected that many will become lost in the progression of obsolescence.

It also troubles me that folks get so caught up in taking a snapshot or video that they don’t truly experience a moment for what it is. A photograph or video will never convey an experience. Credit photographer Sally Mann for expressing that notion in her book that memories are being supplanted by photographs of a slice in time, and not living in the moment and experiencing what is happening in a viewfinder and not actually in front of our eyes. Years from now, we will remember an event as it was, or does the photograph corrupt our memories? I know that I now cannot be sure if some of my earliest memories were what I recall, or what my father’s 8mm movies show.

Where do you see yourself in that world?

I have no idea. I’m too busy shooting pictures, mixing chemicals and coating paper for printing to worry about my miniscule impression on the art world.

Could you tell me your name?

Dan Schlapbach

Where are you from?

Freeland, MD (about a mile south of the PA border)

How did you get into photography as an art medium (as opposed to casual or professional use)?

Since the first time I picked up my father’s Lordomat 35mm camera decades ago, I have experimented with the medium. As I advanced through schools and my education I considered various photographic careers, but ultimately decided that a career in photographic education would allow me to keep my artistic photographic practice tangential but not central to my vocation. I have been very fortunate to have the opportunity to use my photographic interests and skills to create art.

Which alternative processes do you practice?

Several (pinhole cameras, cyanotypes, palladium, etc., but wet-plate collodion is my passion). The particular process presented in this exhibition is relievo ambrotype. The relievo ambrotype process is a 19th-century photographic technique that incorporates multiple layers of photographs to create a single image. The foundation of the process is wet plate collodion. The wet plate collodion process is capable of producing different kinds of photographs: it may be coated onto a piece of black metal to produce a tintype; it may be coated onto a piece of glass to produce a negative from which it is possible to make positive prints; or if the processed glass plate is backed with a piece of black material the result is a positive image called an ambrotype.

John Urie introduced the relievo ambrotype in Glasgow in 1854. Relievo refers to a sculptural technique in which shapes project from or recede into a surrounding background. The relievo ambrotype achieved this relief effect by layering the glass collodion image plate over another image or background. This process was used almost exclusively for portraits between the 1850s and 1860s, and the backgrounds (usually fabricated) situated the subjects – e.g. identifying the Civil War soldier in his battlefield, indicating the sitter’s social status, or creating a potentially faux document of a visit to an exotic locale.

What attracted you to alternative processes in general?

Digital photography for me is too quick, perfect and sterile. I have always enjoyed playing with the photographic medium. While this is, of course, certainly possible with digital manipulation (e.g. Photoshop), I prefer to create handcrafted images. I love tactile practices.

What drew you to the specific media you practice?

I have always been interested in 19th-century photography, especially Civil War and Westward expansion photography. Wet-plate collodion was the dominant practice during those years. It still fascinates me to consider the fortitude it must have taken to use this process, which we now view is very cumbersome, to make images soon after battles, or after scaling to a 10,000 foot precipice. Moreover, the process makes truly unique images. While prints may be made from wet-plate collodion negatives, ambrotypes made from this process are one-of-a-kind. The relievo ambrotype allows me the option to play with and blend both 19th-century and contemporary photographic techniques and practices.

How does the choice of media influence your choice of subject matter (or vice versa)?

I am trying to blend the look of the antiquated wet-plate collodion process with contemporary digital imaging. I will often photograph older or timeless objects with the wet-plate process and more contemporary subjects for the digital component.

In today’s mobile, electronic world of instant communication and virtual sharing of images, how important is it to you to create hand-made images?

It is critical to me. While I certainly fully appreciate and love all that digital imaging offers, for my personal practice, digital photography is less fulfilling. I have always loved working in the darkroom and would dearly miss the tactile process of image making. The process helps me to slow down and really study what it is that I am photographing.

Is your choice to practice alternative, hand-made photography a reaction to, a complement to, or not influenced by the world of digital media?

I think it is both a reaction and compliment to digital imaging. I appreciate the speed and flexibility that digital photography offers, but I love the meditative, methodical wet-plate collodion process. It may take me several days to complete a single work. But, the antiquated and contemporary processes complement each other in my works. The relievo ambrotype process allows me to blend antiquated, alternative process with contemporary digital image making techniques.

Do you incorporate digital media into your alternative process work?

Not always, but yes with the digital relievo ambrotypes.

If so, how do you incorporate it? Is it limited to mechanical reproduction technique, or does it inform/shape/influence the content of your work?

Yes, it very much informs the content of my work. While wet-plate is still my passion, I do also love the options that digital imaging offers me. I can manipulate the images in multiple ways.

What role do you see for hand-made/alternative process work in the art world of today? Where do you see yourself in that world?

In the fast-paced, Instagram world in which we live, I think it is important that some artists slow down and use their hands to craft images. Digital imaging, and all that it offers, is fantastic and should be embraced, but it is critical that we not loose sight of the slow, handcrafted image.

Reminder – Rendering The Spirit opens on Friday, May 18, and runs through April 11. The artists’ reception will be held March 26 from 6-8pm at Glen Echo Photoworks, 7300 MacArthur Boulevard, Glen Echo, Maryland, 20812.

Could you tell me your name?

Yugo Ito

Where are you from?

I am from Nagoya, Japan.

How did you get into photography as an art medium (as opposed to casual or professional use)?

Since I was born as a son of the fourth generation of my family-business photo studio, it was natural for me to get into photography. I have completed PGdip in photography at the University of the Art London after completing BA in Management in Tokyo.

Which alternative processes do you practice?

Wet Plate Collodion

What attracted you to alternative processes in general?

Because I thought that I needed to experience the same amount of difficulty taking a photo as photography pioneers had.

What drew you to the specific media you practice?

Because as being one of modern photographers, I felt I must know and respect how photography pioneers invented and developed photography.

And also, I thought that photography would have lost its reliability and its power of assuring the referent’s existence in future if we keep taking photos digitally. It is because, as we all know well, digital photography allows us to easily edit a photograph. Our offspring might not be able to trust our photographs to be 100% like us. The age of that photography tells the truth is over. To be more precise, the age has been already over with the advent of film photography. Thus, I decided to learn Wet Plate Collodion process to restore its essential features.

How does the choice of media influence your choice of subject matter (or vice versa)?

With a big influence of being as a son of the fourth generation of my family-business photo studio, I strongly believe that photography is ultimately a means recording our precious lives, times, things. So, that affects my choice of subject matter.

In today’s mobile, electronic world of instant communication and virtual sharing of images, how important is it to you to create hand-made images?

We feel we want to take a photo when we cannot digest occurrences going by too soon right in front of us. As a result, we are drowning in a sea of abundant photographs. It is a very tough work to pick up what we really want to keep out of them. Have you ever thought that how hard for family members to select which photo to keep or not after you passed away? I experienced such a situation when my grandmother passed away. I think that our impulse to take a photo is almost one of our instincts. Thus, we would need to think to add one more option to solve the problem, which is to create hand-made images. It would make it easy to select photographs for the sake of the future.

Is your choice to practice alternative, hand-made photography a reaction to, a complement to, or not influenced by the world of digital media?

Unfortunately, there were many victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake 2011 who lost their photographs taken over the previous ten years because they were only kept digitally. Although most of the photographs in their digital devices disappeared, many physical photographs such as prints and negatives were saved. This made me realize once again how important not to keep our photographs only digitally.

Do you incorporate digital media into your alternative process work?

I appreciate digital media in that its easiness to record something. Also, being able to store them on a Cloud-based storage system is its merit. So, I don’t suppose that we should choice only one of media.

If so, how do you incorporate it? Is it limited to mechanical reproduction technique, or does it inform/shape/influence the content of your work?

If in Japan, for example, I would like to offer an opportunity to make a physical photograph such as alternative prints, ambrotypes or tintypes by using a digital photograph of customers in order to increase the possibility that their photographs survive on natural disaster such as Tsunami. There is a limit on how many photos you can store on a Cloud-based storage system, and also we can’t trust those digital stuff completely.

What role do you see for hand-made/alternative process work in the art world of today? Where do you see yourself in that world?

Some say that uploading photos onto a Cloud-based storage system is the best way of preserving photographs. It is partly true and I agree with it only for the Tsunami case, etc… However, I strongly disagree with not leaving photos as tangible states. I sometimes wonder that the dignity of time passage mood mostly rising from old tangible printed photos itself would greatly contribute to the dignity of the photography referent. Japan has a unique aesthetics called ‘Wabi-Sabi’ (侘び寂び), which is described as finding beauty in imperfection and impermanent. It is very difficult to express in English. But, if I would translate it, Wabi (侘び) is a mind of accepting withering and lacking and the beauty of simplicity and commonplace things, not from luxurious, gorgeous or flamboyant things. Sabi (寂び) is the beauty from a withered state that comes with age. Wabi is the inner side and Sabi is the outer side. It is the beauty rising from negative sentiments. 侘(wabi) and 寂(Sabi), these Japanese characters are negative meanings. I think that this particular aesthetic represents the dignity and the affection toward aging printed photos. Due to that it has just been around 10 years since the digitized photography wave started, I’ve got questions. How much affection we feel toward old photos does time passage contributes to? Can we have the exactly same feeling by our old digital photos in future? The appearance of photos stored digitally never age.

If once people know the easiness to take a photo by a digital camera, it is difficult to teach them how important to keep physical photos, such as prints. But we learned how fragile digital photographs were from the Great East Japan Earthquake 2011 with a lot of victims. I suppose that hand-made/alternative process works appeal people better than just teaching people how important printing is. These old styles/techniques are new to them. It would be great if people could make a physical photograph in the end. Photographs do not exist for the past, photographs do exist for the future. As long as I treat photography in the art world, These are what I would love to share with people.

A reminder: Rendering The Spirit runs from March 18 to April 11. The opening reception will be held March 26 from 6-8pm at Photoworks, 7300 MacArthur Boulevard, Glen Echo, Maryland 20812.

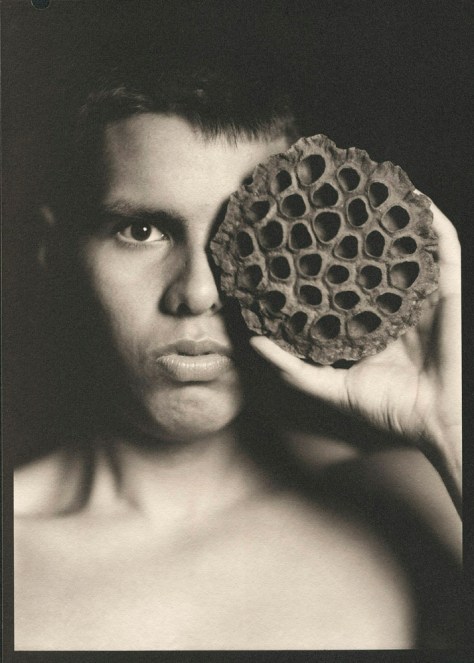

What is your name?

My name is Atalie Day Brown and my husband’s name is Jared Brown.

Where are you from?

I grew up in small-town Cumberland, Maryland and my husband is from Crownsville, MD. We currently live in Pasadena, MD.

How did you get into photography as an art medium?

I have been obsessed with photography since I was a kid. My grandfather was an amateur photographer and I was always inspired by his imagery and talent. I have always been attracted to photography as an art form. Originally, I wanted to become a fine art photographer, it was only when I entered art school/college that I decided to focus more on photojournalism. My husband has had an on-going casual curiosity with photography, but he became more interested while I was going through art school. We decided a few years ago to pursue alternative processes together, as a team.

Which alternative processes do you practice?

We currently create tintypes and ambrotypes

What attracted you to alternative processes in general?

Alternative processes involve a deeper level of intent. It takes additional time and resources to create handmade imagery, therefore you must be purposeful when creating one. You have to consider so many factors and develop a plan. Our tintypes are made using an 8×10 Kodak Studio Camera, circa 1920, and a Petzval lens from 1868; thus, the equipment is large and cumbersome. This process is a labor of love and we appreciate the many aspects of its anatomy.

What drew you to the specific media you practice?

Tintypes have always been an interest to both me and my husband. We love the ethereal qualities tintypes lend to our subjects. Furthermore, the chemical process is a constant challenge, and we (mostly) enjoy combating those seemingly never-ending factors. The historical implications of the medium is also attractive, we love researching pioneers in this field. Another alluring part of the process is the individuality of every single image, no two are ever the same.

How does the choice of media influence your choice of subject matter (or vice versa)?

When creating tintypes, we are constantly debating what subject matter will translate honestly into a tintype image. We select people that are kindred spirits to the process, which can be very divisive. As for still life, we have found that organic matter adds a unique texture to the image. We also enjoy incorporating traditional tintype elements with the modern world.

In today’s mobile, electronic world of instant communication and virtual sharing of images, how important is it to you to create hand-made images?

Creating handmade images in this era of instant-gratification photography is extremely important to us. We are constantly inundated with snapshots, and while they have their place, creating a tangible piece of art using a time-consuming, obsolete medium is truly gratifying.

Is your choice to practice alternative, hand-made photography a reaction to, a complement to, or not influenced by the world of digital media?

Our decision to create alternative photographs is absolutely influenced by current digital media. However, we would have discovered the process regardless of digital media.

Do you incorporate digital media into your alternative process work?

No.

What role do you see for hand-made/alternative process work in the art world of today? Where do you see yourself in that world?

We see alternative processes offering a different avenue for artists who are interested in re-defining alternative mediums in a contemporary manner. I think these handmade processes will become more and more appealing as digital photography continues to dominate. The chemistry and darkroom is a magical place. We just hope to participate in the revival of this medium, one tintype at a time.

Rendering The Spirit opens March 18, with the Artists’ Reception on Saturday, March 26, from 6-8pm at Photoworks, 7300 MacArthur Boulevard, Glen Echo, Maryland, 20812.