In trying to understand the nature of photography, and more specifically trying to come up with a single unifying theory of photography, I think it helps to break it down into two broad overarching categories of photography, specifically as it relates to the notion of “truth”. There is what I would term “informational” photography – photographs whose purpose is to convey information, and any aesthetic considerations are purely secondary, and “aesthetic” photographs where informational content is secondary, if not irrelevant, to the aesthetic/artistic considerations of the image. There is a fluidity between the two, of course – binaries are never absolute – but I think it still helps to have that general categorization to understand an image when looking at it .

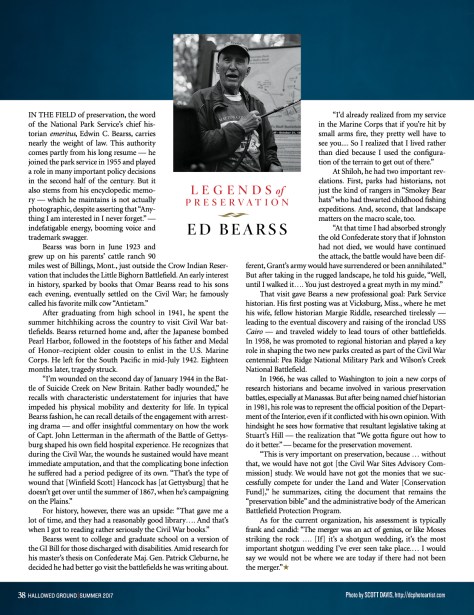

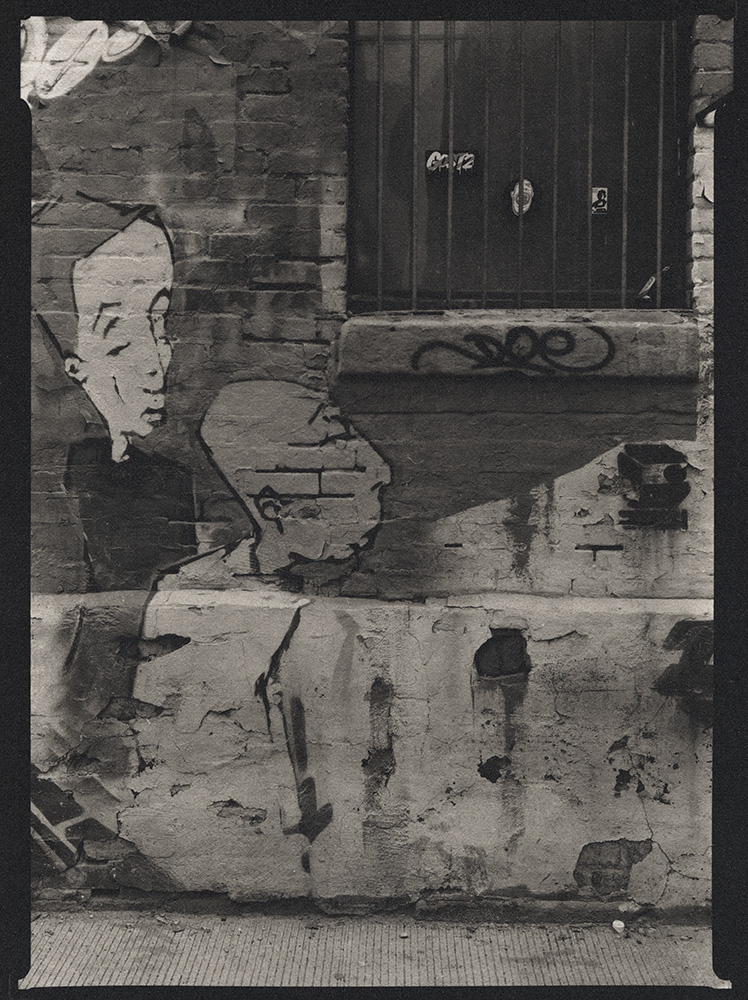

We can look at certain genres of image and understand that they provide clear-cut if not extreme examples of each of these categories – a forensic photograph showing a failed machine part, or a crime scene photograph documenting the state of a room where a murder victim was encountered would be clear-cut examples of photographs where aesthetic concerns are not just in the back seat, they’re in the very last row of the bus when it comes to the priorities of the photographer taking the image.

This is not to say that there cannot be aesthetically pleasing images of failed machine parts or crime scenes; it is just that in these cases, aesthetic qualities are accidental, subconscious, or even generated by the perception of the viewer in an attempt to establish a relationship with the image.

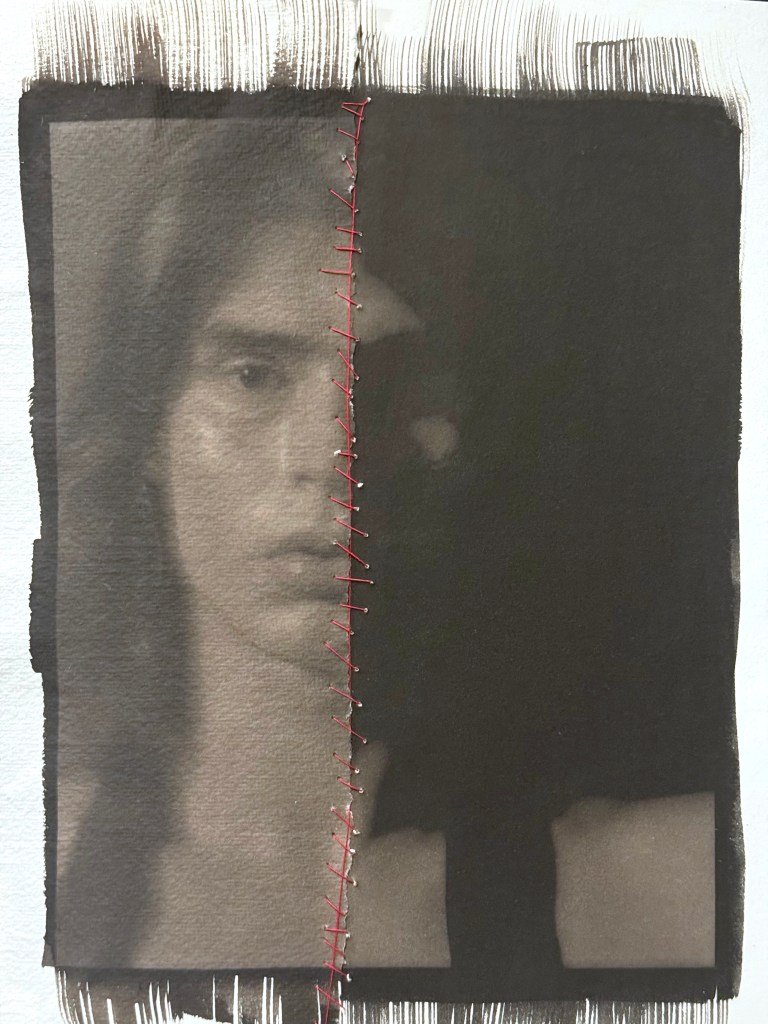

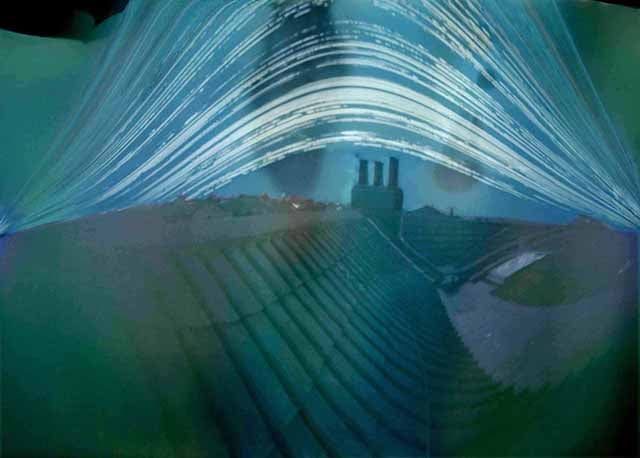

An example of the extreme of an aesthetic image would be something like a chemigram, where no lens has even been involved in the making of the image, the content is purely abstract, and any information gleaned from the photograph is the product of the viewer’s attempt to establish a relationship with the image. Yes, a chemigram may be used clinically to evaluate chemical interactions between light, silver, and developing agents, but that is not the intent.

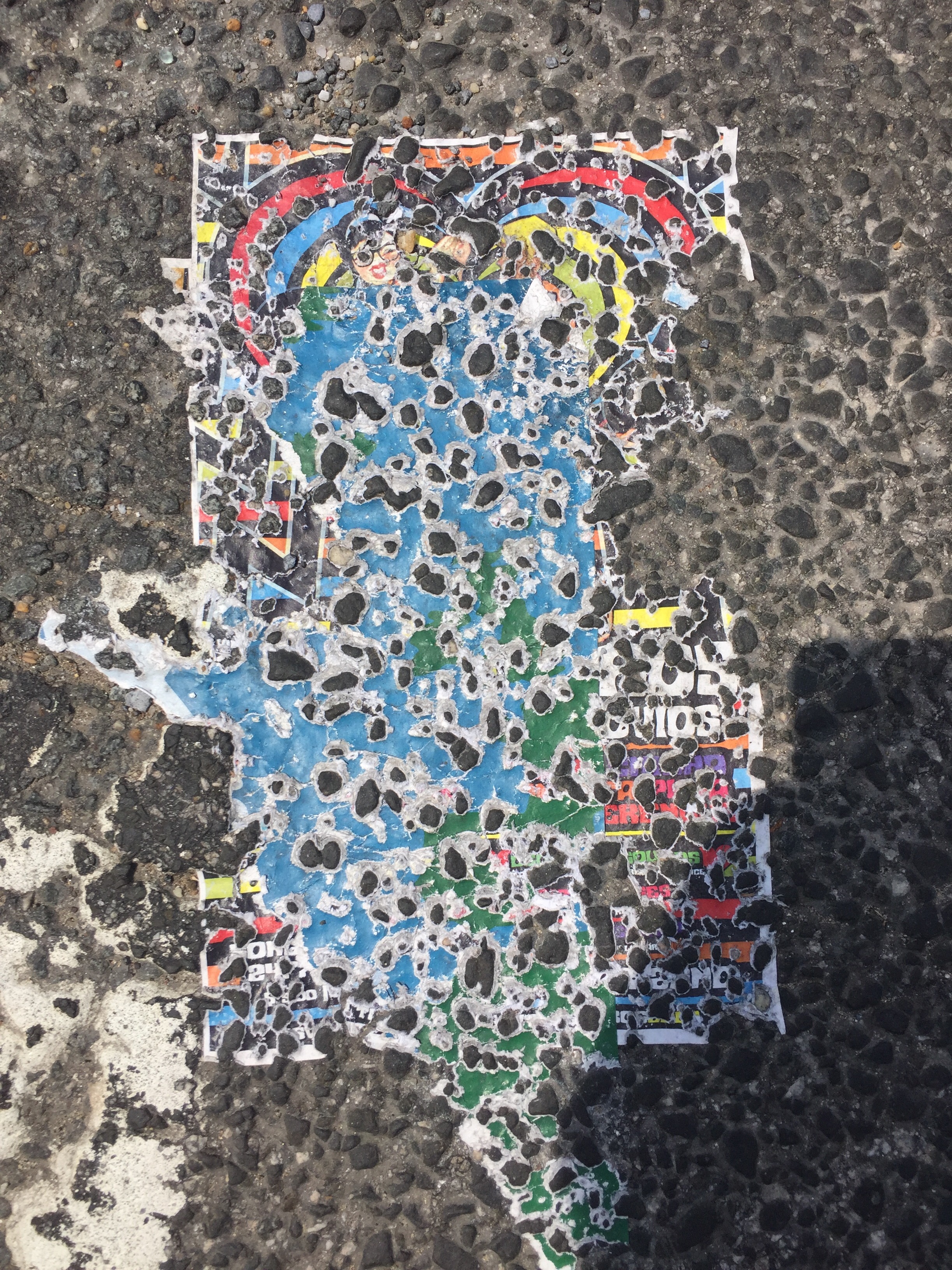

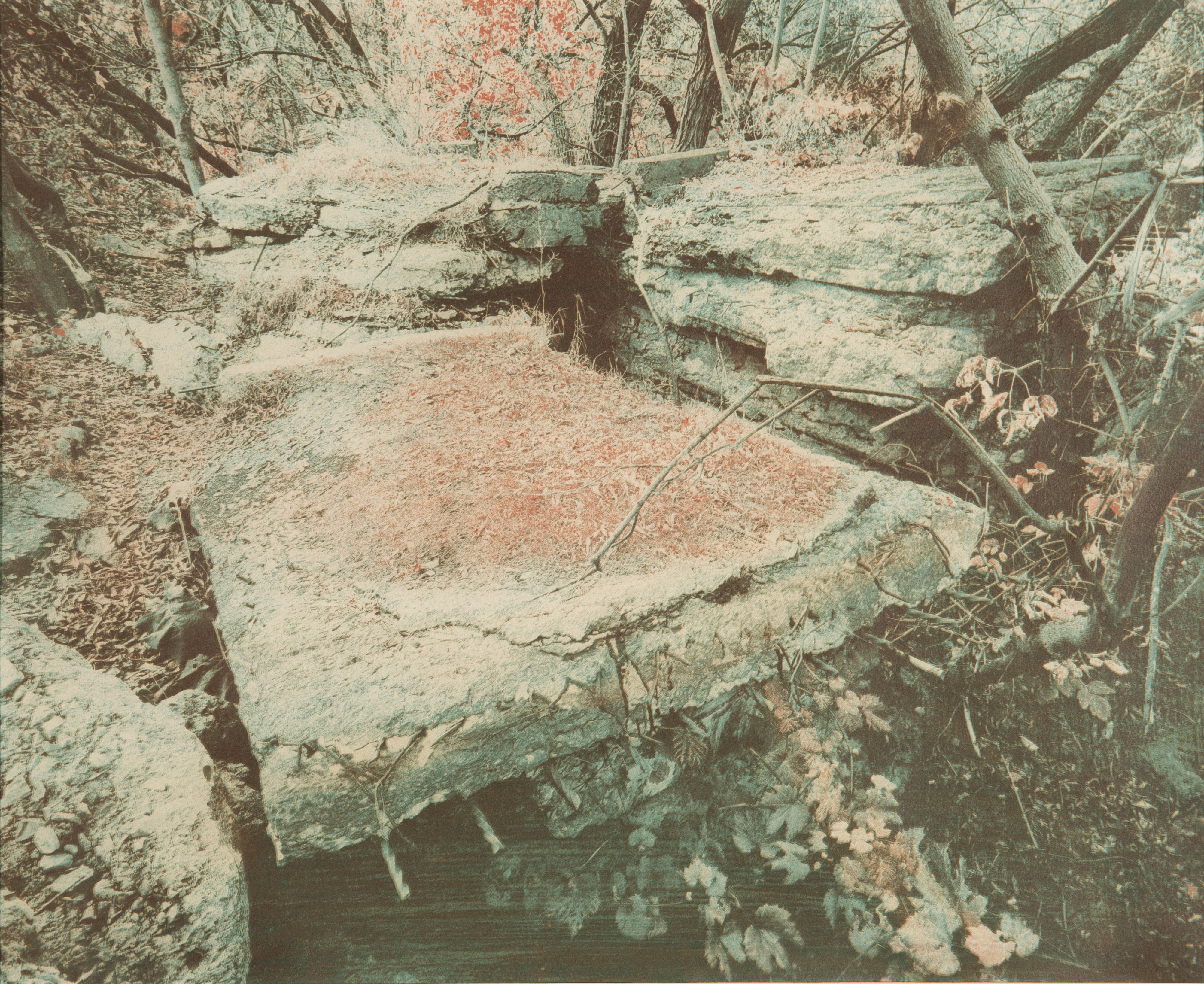

We can start to spiral the drain toward the middle of these two positions looking at other genres of photographs and see that very quickly they take on some aspects of each. You can look at vernacular photographs – “indigenous images made for indigenous purposes”: photographs made for personal consumption, and whose intended audience is purely domestic. Aesthetic concerns, while not the back row of the bus, are still secondary behind conveying basic information (“I was in this place at this time”, “Cousin Sally graduated high school”, or even “there was something about that tree/rock/dent in the car fender that I want to recall in the future”). The “something about this tree/rock/dent” images are so personal that the image functions like Proust’s Madelines; that information is utterly lost to anyone outside the photographer. I can look at a picture of a rock that I took and it immediately brings me back to the summer day in 1975 when I tripped on that rock and chipped a tooth, but anyone else looking at it will be oblivious to that event and wonder why I took that picture of that rock because it has no perceptible aesthetic qualities.

However, it is possible to take that photograph of the same rock with aesthetically pleasing qualities for the same Madeline-esque purpose to trigger my personal memory. At that point though, it begins to cross the line out of an anonymous vernacular – intentional aesthetics imply the intent of a non-domestic audience.

This also relates to the question (which I will deposit here and only briefly touch upon, and return to at a later date) of when does one become a photographer? The term itself is sufficiently broad as to allow for a wide range of photographic activities, from the completely casual (the only photos one takes are family vacation snaps and the dent in the fender of the car to send to the insurance company), the amateur (vacation photos that include more than just record shots of the family in front of various landmarks), the professional (photographs that have commercial value, and therefore are driven by informational AND aesthetic concerns), to the artistic (aesthetic concerns are foremost). Once one starts down the road of photography beyond the completely casual, picking up a camera with intent, that is the moment I would posit that the label “photographer” applies. Of course, once one becomes a photographer of one sort or another, that does not mean that ones role and relationship to photographs is fixed. A professional photographer can take a record shot of their breakfast to show a friend, or some tchotchke in a gift shop to ask their partner about a potential purchase, without involving aesthetic concerns.